This month marks the 40th anniversary of one of television’s greatest history documentary series. Taylor Downing celebrates The World at War.

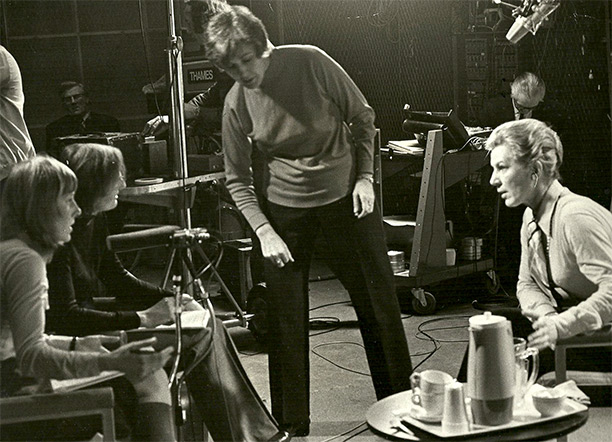

Traudl Junge, Hitler's secretary, breaks her postwar silence in an interview for the series conducted by Sue McConachy and Michael Darlow, left. Production manager Liz Sutherland supervisesOn February 15th, 1971 the Conservative Minister for Posts and Communications, Christopher Chataway, stood up in the House of Commons and announced that the colour TV licence fee was being increased to £12. He then made a momentous announcement affecting the BBC’s commercial rival, ITV. Ever since the public had perceived that ITV was a ‘licence to print money’ the government had put an extra tax on every ITV company, called the Levy. This was a tax on advertising income and, unlike corporation tax (which the ITV companies also paid), the Levy was a tax on revenues and not on profits. The ITV companies had lobbied hard for the removal of the Levy and argued that they would soon have to cut back on new programming, if this money continued to go to the Treasury. The Thames Television company accounts for 1969 recorded a post-tax profit of only £5,609 on revenues of over £15 million. The Conservatives, who had set up the regional ITV system in the mid-1950s, were sympathetic and so Chataway announced a long-term review of the Levy and an immediate halving of it. This effectively gave each ITV company a sudden windfall of cash. Money that was otherwise set aside to pay to the Treasury was instantly available. The only condition was that the cash had to be spent on programmes. For Thames this amounted to at least half a million pounds.

Traudl Junge, Hitler's secretary, breaks her postwar silence in an interview for the series conducted by Sue McConachy and Michael Darlow, left. Production manager Liz Sutherland supervisesOn February 15th, 1971 the Conservative Minister for Posts and Communications, Christopher Chataway, stood up in the House of Commons and announced that the colour TV licence fee was being increased to £12. He then made a momentous announcement affecting the BBC’s commercial rival, ITV. Ever since the public had perceived that ITV was a ‘licence to print money’ the government had put an extra tax on every ITV company, called the Levy. This was a tax on advertising income and, unlike corporation tax (which the ITV companies also paid), the Levy was a tax on revenues and not on profits. The ITV companies had lobbied hard for the removal of the Levy and argued that they would soon have to cut back on new programming, if this money continued to go to the Treasury. The Thames Television company accounts for 1969 recorded a post-tax profit of only £5,609 on revenues of over £15 million. The Conservatives, who had set up the regional ITV system in the mid-1950s, were sympathetic and so Chataway announced a long-term review of the Levy and an immediate halving of it. This effectively gave each ITV company a sudden windfall of cash. Money that was otherwise set aside to pay to the Treasury was instantly available. The only condition was that the cash had to be spent on programmes. For Thames this amounted to at least half a million pounds.

Jeremy Isaacs, the young Controller of Features at Thames, read about the announcement in the Evening Standard and immediately went to see his boss, Brian Tesler. For many months Isaacs had been thinking about a major documentary series on the Second World War. He knew the BBC was considering a series as a follow-on to The Great War, made in 1964. Isaacs wanted to get in there first. Thames Television was the youngest ITV company and had only gone on air in July 1968, taking over from Rediffusion and ABC Television. Serving the London region, it was potentially one of the wealthiest companies in the network. It also had great ambitions to show the other ITV companies, such as Granada and Lew Grade’s ATV, as well as the BBC, that it could make quality programmes. In the distant future there was the possibility of a fourth channel and Thames wanted to prove to the Independent Broadcasting Authority that ITV could produce high quality public broadcasting as good as anything at the BBC, in the hope that the new channel would come to them. A combination of corporate ambition, a sudden windfall of cash and the vision of its senior executives all came together. Within 24 hours Isaacs got approval to produce a 26-part series on the Second World War. It would be the biggest factual series ever made by an ITV company.

The only problem was that when the decision was made there was no script, no treatment and no outline. Jeremy Isaacs immediately set to work. He visited the Director of the Imperial War Museum (IWM), Dr Noble Frankland. The museum had co-operated on The Great War and felt they had been badly treated by the BBC. Frankland even made a formal complaint to the Director-General, Sir Hugh Greene. So he was no friend of television. But he immediately took to Isaacs and his ideas. He later wrote that he had never before met a producer of ‘such brilliance and integrity’. Isaacs could easily have made a series on Britain at war, wallowing in the songs and speeches that kept the nation going from 1939 to 1945. It would no doubt have been very popular to an ITV audience. However what he had in mind was something far more ambitious. He wanted to show how the war affected people’s lives across the whole world. He did not want a military history full of admirals and generals. He wanted a series that would feature Berlin housewives, citizens of Leningrad, people who had been bombed in Coventry and Tokyo, as well as soldiers, sailors and airmen who had experienced the battles that shaped the war. He did not want a series that would celebrate an Anglo-American victory. He wanted to show the war from all sides. Frankland was fired up by this and agreed to act as consultant, as long as Thames would use archive film accurately in the series, unlike the BBC in The Great War, where feature film material had been freely intercut with authentic footage. Isaacs was keen on this and came up with an outline of 26 programme ideas. Frankland commented on them, pointed out some errors and omissions and after some tweaks this outline became the basis of the series. Only two episodes were later dropped and others substituted.

In the long running rivalry between the BBC and commercial television, the announcement that Thames was making a series on the Second World War and that Frankland was consultant was a major triumph for ITV. ‘Auntie Beeb’ believed only it could do history on television. Now a brash young ITV upstart was picking up the baton it had dropped. Egg was dripping off the faces of the BBC executives.

Isaacs then had to prepare costings and recruit staff. The budget came in at £440,000, just enough to keep everyone happy at this stage. Key staff members joined the team: Liz Sutherland, ex-Granada, as production manager; John Rowe, ex-Rediffusion, who had worked on The Life and Times of Mountbatten, as chief film researcher; Alan Afriat, who had edited many This Week current affairs programmes as well as documentaries, as supervising editor. Jerry Kuehl was brought in to act as a sort of quality control officer with regard to the use of archive film and factual material across the series. Over the next few years many directors would be stung by a missive from Kuehl telling them they had used the wrong mark of tank or aircraft in a particular sequence. Raye Farr, another film researcher, found a fabulous stash of unseen archive film at the Bundesarchiv in Germany. And although they did not discover the extraordinary colour material of Hitler and his cronies captured in the Eva Braun home movies, the series made this material available to a worldwide television audience for the first time. The World at War would acquire a reputation for the honest and outstanding use of archive material. Eventually a team of 50 people was recruited. They worked for three years making the series.

Isaacs wanted the programmes to look and feel consistent in their use of interview material intercut with archive footage. But he did not want to impose a rigid format on each show and he wanted every director to bring his own creativity to his particular programme. It is almost impossible to imagine an executive producer today giving such freedom to the directors of a series, while ensuring that every episode was instantly recognisable within the series brand. There were several directors. Peter Batty was a military history specialist. His six episodes contain more generals and field marshals than the others but are among the most effective in the series. David Elstein was a successful young current affairs producer. His episodes introduced new ideas about the war to a British audience; for example, the argument that the Americans dropped the atom bomb as a political statement to overawe the Russians. Martin Smith had been an editor who was promoted by Isaacs to direct his first major documentaries. His episode on the suffering on the Eastern Front is one of the most powerful. Ben Shephard was promoted from researcher to direct an episode. Ted Childs made two episodes. John Pett used the voice-overs of some of his interviews to create a haunting chorus to supplement montages of archive film. Hugh Raggett directed the opening show. Phillip Whitehead somehow combined his job as Labour MP with directing two episodes. Michael Darlow tackled the programmes that included some of the most morally challenging stories, living under occupation and the Holocaust. Jerry Kuehl directed the penultimate episode and Isaacs himself made the final programme in the series. It was a remarkably talented collection of film-makers.

Isaacs wanted to use the device that was then more common in current affairs than in documentaries, with writers working alongside the directors to produce the final commentaries. A distinguished group of writers was signed up, ranging from Neal Ascherson to Charles Douglas Home and from Stuart Hood to Angus Calder. Many of them had no television experience and Ascherson, for instance, remembers having to learn the incredible discipline of writing to picture, something he claims to have benefited from throughout his subsequent career.

Isaacs realised he would need a composer to write original music for the series. He found Carl Davis. It was an inspired choice and his forceful music gave the title sequence a memorable quality that still impresses today. He also wrote hours of music to accompany individual sequences. As the production continued, it was clear to the team who were to sell the series internationally that it had big potential. Isaacs wanted an experienced journalist to read the commentaries, like Robert Kee or Rene Cutforth, but pressure was put on him to select an A-list actor. Eventually he was persuaded to ask Laurence Olivier. It was the first and last television commentary Olivier ever read. He disliked the work intensely. As a physical actor he felt constrained by reading to a microphone in a tiny studio. But without doubt his voice with all his idiosyncratic pronunciations (Stahleen for Stalin; Soviét instead of Soviet) is part of the success of the series.

The whole project was made with a collegiate spirit. Members of the team, including the researchers, were regularly invited to view and comment on each others’ rough cuts. IWM staff were invited to screenings as well. Everyone remembers these open events as challenging but as an exciting part of the production process. The project was based in the Thames studios in Teddington, where the company’s comedy, drama and light entertainment were made. Alongside the earnest documentary makers were production teams working with Tommy Cooper and Benny Hill. Sue McConarchy, one of the researchers, remembered returning from a particularly demanding trip to interview ex-SS officers and sitting down in the canteen next to a man improbably dressed in medieval jousting gear. ‘What are you working on?’ he asked her. ‘The Second World War’ she replied. ‘Oh that’s nice’, he responded. ‘Who’s playing Hitler?’

The series began transmission in both Britain and the United States in October 1973. It had an instant impact on both sides of the Atlantic. Some episodes attracted an audience of ten million. The episode on the Holocaust, ‘Genocide’, created immense controversy. Michael Darlow, the director, used graphic footage of the horrors of the camps, accompanied by interview material not only from the survivors but also from an SS general who in part tried to justify the killings. Mary Whitehouse complained that such footage should not be shown at nine o’clock. Other leading interviewees included Albert Speer, recently released from Spandau prison; Traudl Junge, Hitler’s secretary; Anthony Eden; Curtis Le May and Arthur Harris; and the secretary to the Japanese War Cabinet in 1945. But without doubt the most memorable contribution comes from the host of ordinary people caught up in the extraordinary events of the war – just as Isaacs had intended.

For 40 years The World at War has never been off television screens. There is always a TV station showing it somewhere in the world. It has been sold to more than 50 countries. In Britain and America the rights are fought over every time they come up for renewal. It was made before even the era of the VHS. Now it is dissected on DVDs and on the Internet by students around the world. It has survived the demise of Thames Television, which lost its franchise in 1992. But it still goes on. And the IWM, who did a deal to earn five per cent of overseas sales, continues to receive a healthy cheque every six months.

Why has it endured? The series is thoughtful and intelligent. It was made by an immensely talented team working for an ambitious, wealthy company. It eventually came in 100 per cent over budget. But no one seemed to mind. It showed that commercial companies could produce quality programmes and earn considerable revenues from them. But more than anything, the series has a moral ambiguity about war. It is not about good guys and baddies, winners and losers. It is about the terrible human experience of war. People will still be watching it in 40 years time.

No comments:

Post a Comment