We think of the union of vanity and technology as a modern affliction. Truth is, humans have long pursued that elusive quality known as “beauty” before the miracles of modern medicine. Inventors always devised tools to help women—and men—achieve the physical ideals of their era. Eager test subjects were hooked up to torture machines-like devices, or employ products that contained poison. When it came to results, most were disappointed. While it is easy to laugh at those ridiculous gizmos, modern-day gadgets prove that we are no less gullible than our forebears.

The perfect face

Victorian and Edwardian women had elaborate corsets and hoop skirts to hide and control their bodies, every proper lady desired a wasp-waisted figure and because the body was so well-covered, only the face revealed one’s natural beauty. To be considered truly lovely, a woman was expected to have pale, unblemished skin, soft and supple.

Naturally, innovators got to work developing products to protect and restore precious, youthful skin. In 1889, Margaret Kroesen grew concerned that her daughter Alice, a concert pianist, was developing frown lines—and that those damning wrinkles could hurt her stage career. According to the company’s site, the elder Kroesen came up with a product called Wrinkle Eradicators (now known as Frownies), of unbleached paper strips backed with a vegetable-based adhesive.

The product, still made today, has so saturated modern markets that is ti impossible to find an objective review. The company insists that the tape, a supposed “Hollywood secret,” works by “employing the basic principle of fitness to the muscles of the face.”

While Victorians believed that vibrations could cure everything from constipation to headaches to “female hysteria.” It is not surprising the Fitzgerald Star Vibrator, like the one seen in this 1921 ad from “Hearst’s International” magazine, claimed to fight sagging, sallow skin and to keep muscles firm and healthy.

Show & Teller YardSaleDave found an example of this peculiar type of gadget, in wind-up format, and while Savoychina1 found an advertising pamphlet that claims the Star Vibrator would not only fix your “flabby skin,” it could also treat dandruff, improve muscle tone, and eliminate aches and pains. And if you take a good look at the “To Develop and Strengthen Tissue” illustration, which shows a lady holding the Star Vibrator against her chest, it is clear the text is a euphemism for increasing a woman’s cup size.

The active ingredient for Stillman’s Freckle Cream was mercury. Via ComesticsandSkin.com.

When Coco Chanel got a sunburn on the French Riviera in the 1920s, she made tans cool, but women still wanted to avoid freckles like the plague. They were so vigilant in their fight against this scourge that they covered their faces and bodies with patent-medicine ointments, such as Stillman’s Freckle Cream and Othine Freckle Remover, with dangerous levels of mercury, and wore comical sun-proof masks and capes. Even Amelia Earhardt, known for her high-flying heroics, felt ashamed of her natural speckles, and the possible site of her final landing has been recently identified by a bottle of Dr. C.H. Berry’s Freckle Ointment.

Max Factor (left) and his assistants analyze a woman’s face in 1933. Via ModernMechanix.com.

With the burgeoning movie industry, unbelievably beautiful Hollywood stars became larger than life in the 1930s. It is of no surprise that their flawless close-up mugs became a national obsession. What is it that made them so comely? Can it be measured, analyzed, and re-created at home? Chemist, cosmetician, and wig-maker Max Factor led the charge with this frightening looking device from 1933. While the Beauty Micrometer looks like something out of a “Hellraiser” nightmare, apparently it was pretty innocuous: It measured your face and head to determine where you should apply blush, shadow, and highlights to the greatest effect.

Isabella Gilbert’s Dimple Machine from 1936 and a 1932 Suction Treatment for skin-cleaning. Via ModernMechanix.com.

Modern Mechanix has uncovered several other disturbing 1930s and ’40s beauty devices, including Isabella Gilbert’s metal brace that dug smiley dimples right into your face and a vacuum procedure that claimed to suck the wrinkles out of your skin. The Glamour Bonnet, which inventor Dr. D.M. Ackerman asserted could improve one’s complexion by reducing air pressure around the skin, looked more like the equivalent of putting a plastic bag over your head.

A bodacious body

We already told you about all the strange contraptions people have used through history in attempts to stay effortlessly svelte and fit—from mechanical horses to strange stretching hammocks and vibrating belt machines. Despite any bust-increasing exercises you may have learned of whilr reading the 1970 Judy Blume book “Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret,” you can’t work-out your way to more curves.

Back in the Roaring Twenties, society was scandalized and titillated by brazenly androgynous flappers with their skinny arms, boyish haircuts, and reedy bodies, a liberating rebellion from the tight-laced binds of Victorian propriety. But during the Depression of the 1930s, being thin and malnourished became depressingly common. That’s why, as strange as it seems now, bigger bodies were considered better: Wealthy people were hearty and well-fed. So ads in the 1930s and ’40s promoted “ironized yeast” as a way to “gain 10 to 25 pounds” quickly.

In 1949, the Breathing Balloon promised to help you “develop your form.” Via ModernMechanix.com.

It’s tempting to celebrate these ads as beacon of a body-positive past, a beautiful time before celebrities and models were encouraged to starve themselves. But the truth is, you’ll notice the “10 or 25 pounds” promised in these ads always deposits itself on the women’s breasts and hips in sexy hourglass proportions. In reality, for many women a large part of that promised fat would go directly to the belly. Even then, chubby bellies and expanding waistlines were not idealized by our Hollywood-obsessed culture.

But, hey, hucksters offered other ideas for getting full breasts. Why not inflate them like balloons? All you need is more breathing capacity, right—because your lungs are in your boobs? That’s what the ads for the Breathing Balloon and Psycho-Expander suggest. If that doesn’t work, there was always the Star Vibrator.

For what it’s worth, men, too, were berated for thinness, i.e. being the “90-pound weakling,” in the ’30 and ’40s. Ads for ironized yeast and fitness programs, like the one created by bodybuilder Charles Atlas, promised to turn scrawny nerds into strapping hunks in a matter of weeks.

Luscious hair

When it comes to hairstyles, the fashion consensus about what kind of hair is most lovely has swung wildly between curly and straight. That’s why you have women wrapping their hair in Coke cans one decade, and then flattening their locks with clothing irons the next.

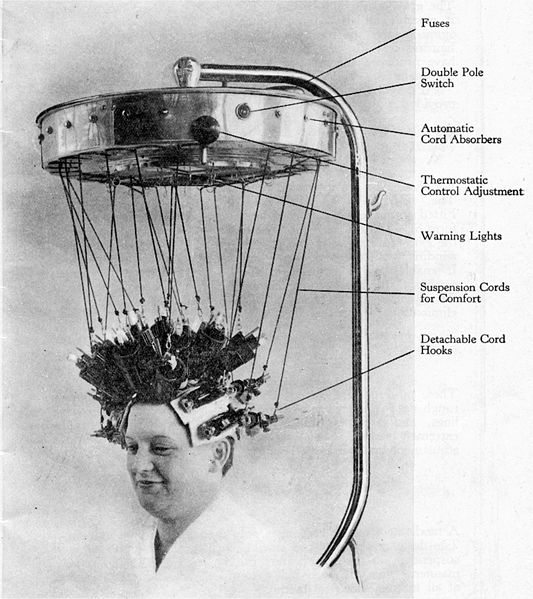

Icall debuted the wireless perm machine in 1934, which was unplugged before the curlers were attached to the head. From “Permanent Waving: The Golden Years” by Louis Calvete.

Perhaps the most freakish mad-scientist-looking beauty device of the 1920s was the permanent waving machine. Designed to give a woman a head of springy curls, it also (temporarily) made her look like the Bride of Frankenstein, waiting for a jolt of lightning. In the late 1930s, the chemical perm was invented, and soon these cumbersome machines were deemed as outdated and scrapped.

Several early mechanical devices intended to cure balding. Via Radio-Guy.com.

Men were not immune to hair vanity. According to our friend Steve Erenberg in his Industrial Anatomy newsletter at Radio-Guy.com, Victorian scientists believed that increasing blood flow to the head could cure baldness. Before hair plugs and Rogaine, men with receding hairlines donned crazy caps with heaters, head pumps, and vibrators in hopes of growing a new lush head of hair.

The original 1986 Epilady Epilator.

On the flip side, men and women have long faced the laborious task of removing unwanted hair. In 1986, the Epilady, promoted in teen magazines as a leg-shaving alternative, was all the rage. Its vibrating metal coil did, in fact, do what it promised: Pull out individual hairs but it hurt like hell. Today, we have something called the No! No!, which burns each strand down to its roots using “heat transference.” The No! No! promises “virtually” no pain, as long as you aren’t sensitive to the stench of smoldering hair.

No comments:

Post a Comment