Who will make the better Gatsby? Will DiCaprio convince in a pink suit as Robert Redford did in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 adaptation? As eager audiences race to the cinemas, there is one Gatsby film we will not be making comparisons to. Very few are aware of the original screen adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel. For several decades, the 1926 silent film by Paramount Pictures had ceased to exist.

All that remains of the original 80-minute film is a one-minute trailer.

Scott and Zelda saw the film, and in an undated letter Zelda allegedly wrote: “We saw ‘The Great Gatsby’ in the movies. It’s ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left.”

Perhaps forgettable in style, but why was the film physically

forgotten. The first Great Gatsby is just one of countless vanished films, “gone missing” from any known film

archives or private collections. Sadly, more American silent films

have been lost than have been preserved and over half of

sound films made in the U.S between 1927-1950 have vanished as well. It is

estimated that more than 90% of films made before 1929 no longer exist.

The Academy’s Lost Films…

An Oscar nominee for Best Picture in 1928, The Patriot, and The Way of All Flesh, for which Emil Jannings won Best Actor in 1927, are both lost in time.

The British Film Institute made a list of the 75 “Most Wanted” lost films and at the top is Alfred Hitchcock’s 1926 silent film, Mountain Eagles, which went missing during his lifetime.

Hitchcock filming The Mountain Eagles, courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Hitchcock apparently hated the film so much he was glad it was gone– making its disappearance even more suspicious. He would not be the first filmmaker to destroy his own work. After director Robert Hartford-Davis’ Nobody Ordered Love (1972) was poorly promoted and critically panned, all known copies are believed to have been destroyed upon his death and at his request, the film is also listed on the British Film Institute’s Most Wanted list.

(c) Neil Pardington

Overly self-critical directors are not the cause of motion pictures disappearances. In many cases, films were destroyed in fires. Before 1952, the 35 mm negatives and prints used a highly flammable and chemically unstable nitrate film. At Fox Pictures in 1937, a storage vault fire destroyed the entire archive of original negatives from their pre-1935 movies.

Nitrate film needs a storage environment of low humidity and temperatures

with adequate ventilation to stave off decay or disintegration

into powder akin to gunpowder, able to spontaneously combust.

(c) Gert Moberg

The real cause of film loss was by deliberate destruction. Storage vaults and conditions as described above were expensive and as the era of silent films ended, its films had little commercial value for big studios. These were the days before televisions and home videos, when movies could be seen over and over and money would pour into producers’ pockets years after the premiere of a film.

The studios intentionally binned

them. Many were melted for silver and some were broken down into

short clips and sold as novelty items to film-lovers to play

their favourite movie scenes on home projectors at parties.

To

grasp how many films of this era were destroyed, we must consider

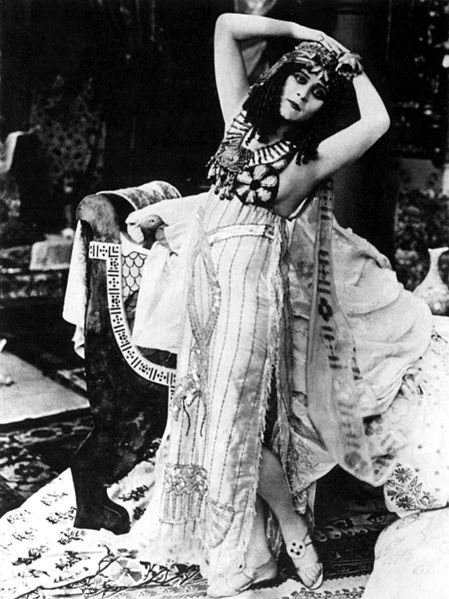

Theda Bara, the best-known actress of the early silent era. She made 40

films including the original Cleopatra and Romeo and Juliet. Only three and a half of those survived.

To

grasp how many films of this era were destroyed, we must consider

Theda Bara, the best-known actress of the early silent era. She made 40

films including the original Cleopatra and Romeo and Juliet. Only three and a half of those survived.

This careless loss of cinema did not happen only in Hollywood and the British film industry. The world’s

first-ever animated feature film with sound, an Argentinian production

called Peludópolis was lost, as well as two iconic Japanese

monster flicks, preceding Godzilla by more than a decade. In 1967, an

unofficial but popular Batman Fights Dracula, was made in the

Philippines without the copyright permission of DC comics. This great

contribution to cinematic history sadly did not survive either!

Censorship also contributed to films going missing, especially during wartime. In 1938, the Nazi regime seized Nad Niemmen,

a highly praised film adaptation of a classic Polish novel. Although

the Nazis appeared to appreciate the artistic value of the movie, they

could not allow the screening of a picture so firmly rooted in Polish

history. It was dubbed and re-edited to serve as pro-German propaganda.

Polish underground resistance took the remaining original copies of the

film and hid them in the winter of 1939. They have never been found.

Censorship also contributed to films going missing, especially during wartime. In 1938, the Nazi regime seized Nad Niemmen,

a highly praised film adaptation of a classic Polish novel. Although

the Nazis appeared to appreciate the artistic value of the movie, they

could not allow the screening of a picture so firmly rooted in Polish

history. It was dubbed and re-edited to serve as pro-German propaganda.

Polish underground resistance took the remaining original copies of the

film and hid them in the winter of 1939. They have never been found.The Lost Film that was Found in a Janitor’s Closet

There is a happy and remarkable ending for a very famous and censured French film, thought destroyed and lost forever, it turned up in a janitor’s closet in Norway decades later.

The Passion of Joan of Arc, weathered several cuts by order of the Archbishop of Paris and again by nationalist government censors in 1928. The film’s Danish director, Carl Theodor Dreyer, had no say in the cuts. Their reason? Dreyer was not Catholic or French and “to let this be made in France would be a scandalous abdication of responsibility.” Later that year, the film’s original negative was destroyed by fire. Dreyer was able to patch together a new version of his original cut using alternate takes but shockingly, this version was also destroyed in a lab fire in 1929. Copies of Dreyer’s second version were almost impossible to find and the original was believed to be lost forever. After his death, Danish filmmakers attempted to cut together scenes from different available prints and create a version as true to his original cut as possible, but in 1981, the impossible happened.

An employee of a mental institution in Oslo, the Dikemark Sykehus, found several old film canisters in a janitor’s closet labeled as The Passion of Joan of Arc. They were sent to the Norwegian Film Institute but gathered dust for three years before someone finally examined them and discovered they were indeed Dreyer’s original cut prior to the government and church’s censorship. No records have been found of the film’s shipment to Oslo, but it is believed the director of the institution, who was also a published historian, may have requested a special copy for safekeeping.

Do not assume your

favourite films are safe because we have updated systems since the

1950s. As recently as 1987, a Quentin Tarantino film, My Best Friend’s Birthday was

partly destroyed in a fire and only 36 minutes of the 70 minute-long

film survived. Tarantino is rumoured to have kept what remains of the

film in his possession.

Scandalously, in 1980, Paramount tried to have all copies of James Dearden’s film Diversion destroyed after they bought the rights to remake it as Fatal Attraction.

Should we still be as eager to get rid of those VHS tapes gathering dust in the attic?

No comments:

Post a Comment