de bene esse: literally, of well-being, morally acceptable but subject to future validation or exception

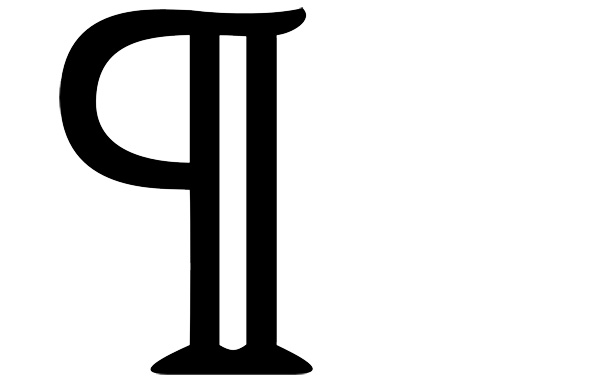

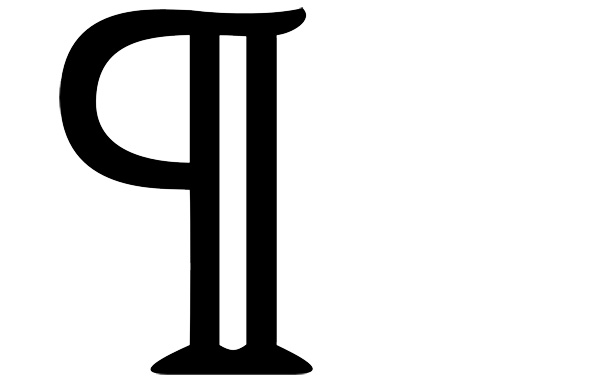

The pilcrow. The derivation of its name is as complex as its form. It originally comes from the Greek paragraphos(para, “beside” and graphein, “to write”), which led to the Old French paragraph, which evolved into pelagraphe and then pelagreffe. Somehow, the word transformed into the Middle English pylcrafte and eventually became the “pilcrow.”

Here on Design Decoded, we love exploring the

signs,

symbols and

codes

embedded in everyday life. These nearly ubiquitous icons and ideograms

are immediately identifiable and may be vaguely understood, but their

full meanings are known only to a select few equipped with specialized

knowledge, and their origins are often lost to history. Software

engineer and writer

Keith Houston loves such symbols, too. In his book,

Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols & Other Typographical Marks,

he looks into, well, the secret life of punctuation, symbols and other

typographical marks. Most of them are familiar, like “quotation marks”

and the @ symbol, but others are less widely used, such as the

interrobang and the manicule. The fascinating study in obscure

typography opens with the single symbol that inspired the entire book, a

symbol that has ties to some of the greatest events in human history,

including the rise of the Catholic Church and the invention of the

printing press: the pilcrow. Also known as the paragraph mark, the

pilcrow, for such a humble, rarely used mark, has a surprisingly complex

history. Indeed, as Houston writes, the pilcrow is “intertwined with

the evolution of modern writing.”

I’ll spare you the earliest history of writing and skip to 200 A.D.,

when “paragraphs,” which could loosely be understood as changes in

topic, speaker or stanza, were denoted by myriad symbols developed by

scribes. There was little consistency. Some used unfamiliar symbols that

can’t easily be translated into a typed blog post, some used something

as simple as a single line – , while others used the letter K, for

kaput, the

Latin word for “head.” Languages change, spellings evolve, and by the

12th century, scribes abandoned the K in favor of the C, for

capitulum (“little head”) to divide texts into

capitula (also known as “chapters”). Like the

treble clef,

the pilcrow evolved due to the inconsistencies inherent in

hand-drawing, and as it became more widely used, the C gained a vertical

line (in keeping with the latest rubrication trends) and other, more

elaborate embellishments, eventually becoming the character seen at the

top of this post.

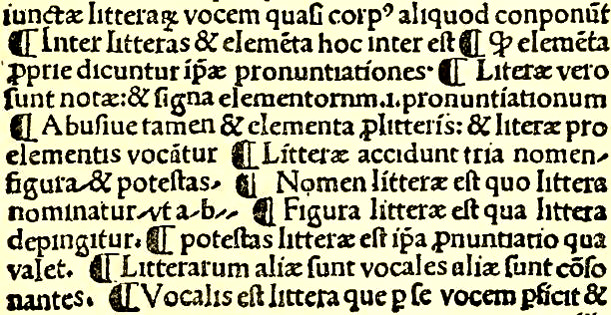

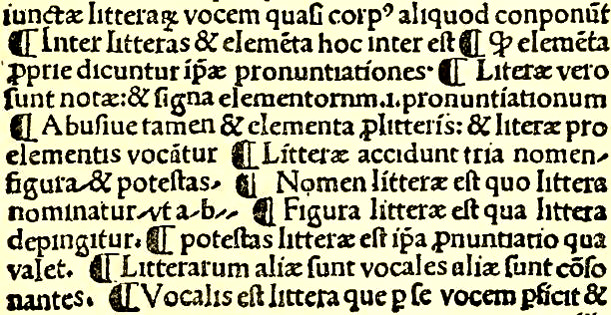

Excerpt of a page from Villanova, Rudimenta Grammaticæ showing several pilcrow signs in the form common at that time, circa 1500 (image: Wikimedia commons).

How did the pilcrow, once an essential, though ornate, part of any

text, become an invisible character scribbled by editors on manuscript

drafts or relegated to the background of word-processing programs? As

Houston writes, “It committed typographical suicide.” In late medieval

writing, the pilcrow had become an ornamental symbol drawn in elaborate

style, often in a bright red ink, by specialized

rubricators,

after a manuscript had been copied by scribes, who left spaces in the

document explicitly for such embellishments. Well, sometimes even the

most skilled rubricator ran out of time, leaving pages filled with empty

white spaces. As

Emile Zola wrote,

“One forges one’s style on the terrible anvil of daily deadlines.”

Apparently the written word itself can be forged on the same anvil.

The problem was only exacerbated by the invention of the printing press.

Early printed books were designed to accommodate hand-drawn

rubrications, including spaces at the beginning of each section for a

pilcrow. As demand grew for the printed word and production increased,

rubricators just couldn’t keep up and the pilcrow was abandoned, though

the spaces remained.

This brief overview only touches on the pilcrow’s fascinating history. If you like our articles on

music notation,

Benjamin Franklin’s phonetic alphabet or even the secret language of

cattle branding, check out

Shady Characters.

No comments:

Post a Comment