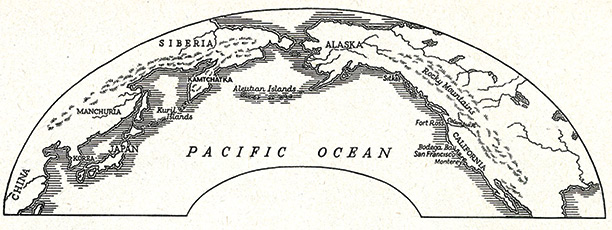

Owen Matthews revisits two articles, one of them from the earliest days of History Today, on Russia’s American empire.

The

story of imperial Russia’s attempt to colonise America is one of

history’s oddest back-corners: by 1812 the southernmost outpost of the

tsar’s dominions was in Sonoma County, just 70 miles north of San

Francisco. Russia also – briefly – had a colony in Hawaii. In the end

Russia’s American empire turned out to be an epic commercial and

imperial failure: Tsar Nicholas I’s refusal to accept large swathes of

modern California, which the newly-minted Republic of Mexico offered in

exchange for arms and diplomatic recognition in 1827, must count as one

of the worst political and economic decisions ever made.

The

story of imperial Russia’s attempt to colonise America is one of

history’s oddest back-corners: by 1812 the southernmost outpost of the

tsar’s dominions was in Sonoma County, just 70 miles north of San

Francisco. Russia also – briefly – had a colony in Hawaii. In the end

Russia’s American empire turned out to be an epic commercial and

imperial failure: Tsar Nicholas I’s refusal to accept large swathes of

modern California, which the newly-minted Republic of Mexico offered in

exchange for arms and diplomatic recognition in 1827, must count as one

of the worst political and economic decisions ever made.History Today published an article about this strange tale in its very first volume, in 1951, when George Edinger noted that ‘the first Europeans to foresee the possibilities of California were Russians, who came across Siberia and felt their way down the Pacific coast’. In 1992 Jeffrey Miller returned to the topic, writing about Russia’s great imperial misfire as ‘a saga of discovery, courage, cunning, misfortune, misdeed and missed opportunities’. Both are excellent essays but, oddly, both are very thin on Russian sources.

There are several interesting reasons for this. First and foremost, to doctrinaire Marxist historians the history of Russian America embodied all that was worst about capitalism. Russia’s American colonies were founded by violent Cossack merchant-adventurers and were based on an economy of confiscation from the docile Aleut natives and, later, the worst excesses of imperialism. By 1818 Russian America was under de facto government admin-istration, with all the corruption, inefficiency and lack of initiative that entailed, and successive Russian rulers failed to realise their American colonies’ extraordinary potential.

Stalin had deemed some parts of Russia’s imperial history politically correct. Peter the Great, for example, was depicted by Soviet historians and film-makers as a kind of proto-Stalin, dragging Russia kicking and screaming into the 18th century. Alexander Nevsky, the Grand Prince of Kiev, who defeated the Teutonic Knights in 1242, was cast as a heroic vanquisher of German aggression. But Russian America had no heroism to it in the opinion of Soviet ideologues, only grubby business interests followed by the dead hand of tsarist bureaucracy.

By the mid-1980s attitudes began to change. The Soviet Union’s first rock opera, Junona i Avos (1981), was a retelling of the real-life love story of Nikolai Rezanov, an aristocrat and adventurer who visited San Francisco in 1806 and became engaged to Conchita, the daughter of the Spanish governor. The perestroika-era production featured a vast icon of the Virgin Mary looming over the actors and haunting Orthodox liturgy. There were references to the ‘Lord Emperor’, and the tsarist flag was raised in triumph at the finale. As Russians awoke to the disintegration of the Soviet Union, here was a nostalgic story of a lost empire in America. As Gorbachev pressed for détente with the West, the romance of Rezanov and Conchita reminded people that love could cross national boundaries and conjured up a romantic vision of pre-Soviet Russia, even as audiences began to contemplate the reality of a post-Soviet Russia.

Starting in the 1990s, Russia’s American empire became a kind of nationalist touchstone. In 1992 the patriotic pop group Lubeh – a favourite of Vladimir Putin – produced a song called ‘Don’t Fool Around, America’, with a chorus which went ‘Siberia and Alaska are two joined shores’ and lyrics berating ‘Katya’ for selling Alaska to the Americans (though it was not Catherine the Great but Alexander II who sold the territory in 1867, for two cents an acre, after Britain’s Lord Palmerston refused to buy it). Today there is a thriving group of Russian historians producing excellent studies on Russian America; Alexander Petrov of Moscow University, for example, broadcasts regular radio programmes on the subject. The subtext of modern Russians’ interest is a kind of post-imperial nostalgia for a lost empire. Better rose-tinted nostalgia, perhaps, than indifference.

Read the original articles:

Russia in California

California's Tsarist Colony

No comments:

Post a Comment