Housed in the same building as Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night” and Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” is a simple paper coffee cup sleeve. It can be found not in the café at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), but rather in the museum’s collections alongside renowned works of art worth millions. But it would be wrong to consider it out of place; the genius of the coffee cup sleeves makes it a million-dollar object as well.

For many, the morning ritual wouldn’t be complete without standing in line at a nearby coffee shop, placing an order with a frazzled cashier managing the A.M. rush and watching the barista pour the coffee, slap a slid on top of the cup and slip a cardboard sleeve over it. It’s a simple and logical ritual, but without that sleeve, what would have happened to our to-go coffee culture? In 2005, MoMA paid tribute to this ingenious design defining the modern American coffee tradition when it acquired a standard coffee cup sleeve for the exhibit “SAFE: Design Takes on Risk,” which featured products that were created to protect. The sleeve takes pride of place at MoMA, alongside Post-It notes, Bic pens and Band-Aids in a collection called “Humble Masterpieces.”

“The reasons for inclusion were very straightforward: a good, sensible, necessary, sustainable (by the standards at that time) solution for a common problem,” says MoMA’s curator Paola Antonelli of the cup sleeve. “While modest in size and price, these objects are indispensable masterpieces of design, deserving of our admiration.”

Like the inventors behind the other “humble masterpieces,” the man behind the sleeve is no artist, but an innovator. Jay Sorensen invented the Java Jacket in 1991 as a solution to a common problem—hot coffee burns fingers. The idea emerged in 1989 when he was pulling out of a coffee shop drive-through on the way to his daughter’s school and a coffee spill burned his fingers, forcing him to release a scalding cup of coffee onto his lap. At the time, he was struggling as a realtor in the years since closing his family-owned service station in Portland, Oregon. While the coffee accident was unfortunate, it gave him the germ of an innovative idea: there had to be a better way to drink coffee on the go.

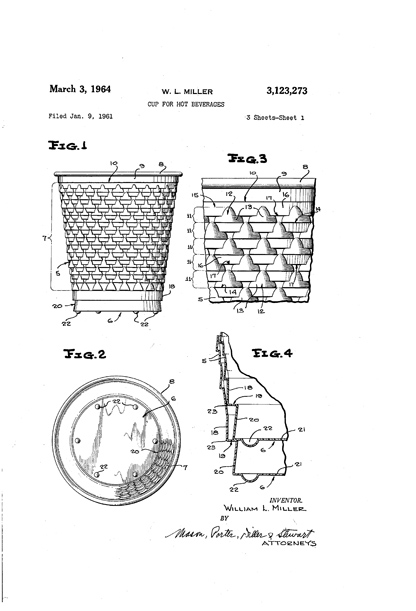

One of Sorensen’s predecessors filed a patent for this cup to hold hot beverages. Image courtesy of USPTO

Sorensen can’t say how he hit upon the idea for the cup sleeve. “It was kind of an evolution,” he says. He used embossed chipboard or linerboard after nixing corrugated paper because of the price point. (Starbucks, who obtained their own patent after Sorensen got his, used the more expensive corrugated paper on the inside of their cup sleeves and smooth paper on the outside.)

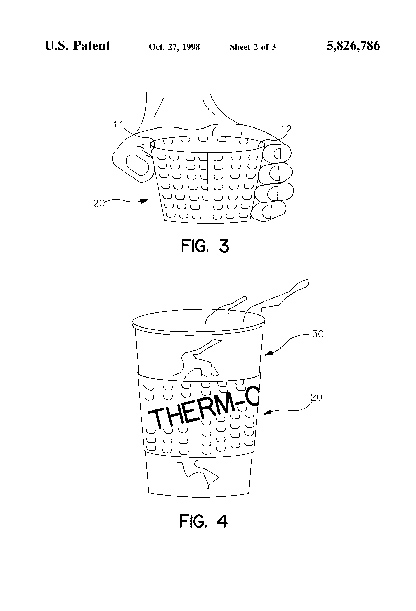

A close-up of the insulation of Sorensen’s coffee sleeve in his patent file. Image courtesy of USPTO

Success accelerated from there. In the first year alone, he enlisted more than 500 clients who were eager to protect the hands of their coffee-driven customers. Today, approximately 1 billion Java Jackets are sold each year to more than 1,500 clients.

Sorensen’s solution was simple and the problem so common that he was not surprised by the demand. “Everybody around me . . . was shocked,” he says. “I wasn’t.”

Although he is now among the most successful, Sorensen is not the first to patent a cup sleeve. Designs date back to the 1920s for similar devices. James A. Pipkin’s 1925 design was a sleeve for beverages in cold glass bottles and Edward R. Egger patented a “portable coaster” in 1947 that fit around a cup. Both were inspired by embarrassing and awkward situations relating to unwanted condensation from cold glass bottles.

A look at Egger’s patent for a portable coaster for a coffee cup. Image courtesy of USPTO.

It’s possible that the standard paper coffee sleeve will be eclipsed by even more environmentally friendly reusable coffee sleeves, or even an end to the paper cup. Sorensen is facing a patent renewal process. And has the sleeve inventor got any new inventions up his sleeve?

“I think we’re just on this train until the tracks come to an end,” Sorensen says.

No comments:

Post a Comment