When Charles L. Hoskins arrived in Savannah in 1975, he was dismayed at the lack of historical records concerning Savannah’s black history.

“When I came here, I went to a workshop on the black history of Savannah,” he says. “I was mortified that I left without a piece of paper.

“What fascinates me is what went on in this place before I arrived,” Hoskins says. “What did I miss out on?

“What struck me when I got here is the lack of stories and narratives. Nobody was writing stuff down. I felt someone had to do it.”

Hoskins set about gathering all the information he could find. Today, his home office is lined with hundreds of books, binders of newspapers, documents and records.

The author of eight books, Hoskins’ most recent is “W.W. Law and His People: A Timeline and Biographies,” a treasure trove of facts, figures, dates, photographs and biographies. It took him six years to complete, but it was a labor of love.

“Some people fish, some golf,” Hoskins says. “Digging up stuff is my hobby.”

The Savannah Morning News and other newspapers from over the decades provided information.

“Most of my stuff came from the papers,” Hoskins says. “The alternate title of my book is ‘The Book of Black Savannah.’”

Westley Wallace Law was a civil rights leader from Savannah. He was president of the Savannah chapter of the NAACP and founder of the Savannah-Yamacraw Branch of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History, the Ralph Mark Gilbert Civil Rights Museum, the King-Tisdell Cottage Museum, the Beach Institute of African American Culture and the Negro Heritage Trail Tour.

Law, who died in 2002 at the age of 79, loved Savannah and its history and wanted to share it with everyone.

“When W.W. Law died, a library was lost,” Hoskins says. “Nobody could do everything. He did what he could. It is important to leave history to posterity.”

There are others who have carried Savannah’s black history with them and shared it with others. In his book, Hoskins cites Frank H. Bynes, a local funeral director, as a “griot,” or storyteller.

“If he was alive, he would still be telling his stories about black Savannah,” Hoskins says.

To Hoskins, the most important aspect of black history in Savannah is the fact that while African Americans arrived in slave ships, today they hold key positions in the city.

“What is fascinating to me is the story of blacks landing on River Street and steadily climbing to City Hall,” he says.

Originally from Trinidad, Hoskins has lived in Italy, England and Spain.

“I came to Savannah to become rector of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church,” he says. “In Montclair, I was the rector of Trinity Episcopal Church. A man told me they were looking for a priest in Savannah. I said, ‘Where is Savannah?’”

In 1875, 100 years before Hoskins’ arrival, St. Matthew’s had a rector who came from Barabdos.

“I was the second one from Trinidad,” he says. “After my first sermon here, a little boy said I talked funny. I said, ‘100 years ago, the rector who spoke had the same accent.’”

In 1980, Hoskins wrote his first book. His works include “Saints Stephen, Augustine and Matthew: 150 Years of Struggle: Hardship and Success,” “Out of Yamacraw and beyond: discovering Black Savannah,” “Yet With a Steady Beat: Biographies of early Black Savannah,” “African American Episcopalians in Savannah: Strife, Struggle and Salvation, 1750-1993,” “The Trouble They Seen: Profiles in the Life of Col. John H. Deveaux, 1848-1909,” “Black Episcopalians in Savannah” and “Black Episcopalians in Georgia.”

“There is no such thing as black history, it’s all history,” Hoskins says. “In Savannah, we don’t have a tale of two cities, we have a city with two tales.

“You can’t separate them,” he says. “You can’t talk about one and not the other.”

For a time, Hoskins worked as a tour guide to share black history to visitors.

“Someone asked me one time if there are more ghosts in Savannah than anywhere else,” he says. “I said, ‘I don’t know if there are more ghosts in Savannah, but Savannah has better storytellers.’”

Sadly, much history has been lost. Not all of it can be saved, Hoskins says.

“The majority of what happened today is lost forever,” he says. “Somebody will pick out one or two things that are important, but the rest will be lost.

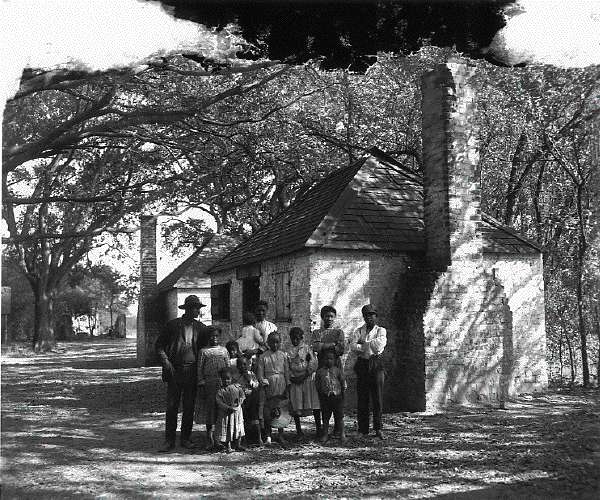

Media type: photograph

Museum Number: LC-D4-34666

Annotation: A large African American family standing in front of former slave quarters at the Hermitage plantation in Savannah, Georgia, in 1907.

Year: 1907

“What we remember is selective. History is not a carbon copy. We reconstruct what happened. Tradition and oral histories are equally important.”

Hoskins knew Law and greatly admired him.

“I would really like to write his life story,” he says. “He was very abrasive. He could drive you up a wall. But he was committed, serious and focused.

“He was a pitbull. He was self-propelled. He was a doer.”

It was Law’s destiny to be a leader, Hoskins says.

“W.W. Law and His People” is available in local bookstores and at the Savannah Visitors Center. “I think it’s a type of book that was needed,” Hoskins says.

“It’s a reference book with things I heard, read and what people told me about the black history of Savannah,” he says. “If I had the money, I would put one in every black home in Savannah. Many black people don’t know or want to know their own history.”

As for Law, Hoskins says he would have criticized the book. “He’d say, ‘For a man not from Savannah, it was all right,’ but it would not be exactly what he thought could be done.”

‘W.W.’ a little book with a powerful message

In 1995, Ja A. Jahannes interviewed W.W. Law.

“The reason I wanted to interview him was because I was going to do the first W.W. Law Lecture at the Savannah Black History Festival,” Jahannes says. “The interview took place in my car.

“He didn’t drive, so I would give him rides. I knew when he died people would tell all kinds of stories and I preferred that they come from his own lips.

“One day, he asked me to pick him up and I took my portable, handheld Dictaphone,” Jahannes says. “I had him tell me about his life from childhood.”

Later, Jahannes did a second interview while sitting on Law’s front porch at his house on Victory Drive.

“He was born into poverty and his father died early,” Jahannes says. “He talked about how his mother guided his development. His grandmother was a great storyteller. Her stories were about how people should live together and get along.”

Recently, Jahannes wrote “W.W.,” a children’s book about Law and his life. It features colorful illustrations by Darrell Naylor-Johnson, a professor at the Savannah College of Art and Design.

“It’s a little book, but I hope it is a little book with a powerful message,” Jahannes says. “The function of the book is to tell the story of his childhood to adulthood and how proper nurturing from parents and grandparents and the community working together can help a child grow up to be a respectable, admirable person.

“He was a larger than life individual,” Jahannes says. “Savannah made him and the South made him. I wanted to pass his story along to the children.”

Jahannes says the book is for everyone.

“The story is written so that it can be understood not only by children, but also make a point to adults,” he says.

The book is told from the point of view of a 10-year-old.

“As a child, he lived on Bismarck Court in a shotgun house behind the Abyssinian Missionary Baptist Church,” Jahannes says. “He learned from games and playing with his sisters, Dorothy and Tess, how to be responsible.”

Law’s grandmother was a huge influence.

“His grandmother loved books and read to him all the time. She did shadow puppets for him. That’s how he became a storyteller.”

It was Law’s grandmother who taught him about racial issues and social justice.

“He learned how blacks and whites both used discrimination,” Jahannes says. “That was pivotal in his desire to work for the civil rights movement.”

In 1961, Law, was fired from his job at the U.S. Postal Service because of his activism in civil rights.

“What makes him notable not only as a Southern standout in the civil rights movement but also on the national one was President Kennedy intervening on his behalf,” Jahannes says.

“Martin Luther King used to come to Savannah. He had a great appreciation of W.W. Law.

Jahannes has his own publishing company, Turner Mayfield Publishing. “W.W.” can be ordered at www.wwlawbook.com.

“I really want to make it available to schools and libraries and community centers,” Jahannes says. “We do ask people to make contributions and not just buy the book.”

Jahannes goal is to raise enough money to keep his personal collection of interviews, lectures and other documents concerning Law in Savannah.

“The city of Atlanta is building a new civil rights museum and has asked for them,” he says. “I would very much like to see all of the things I have on W. W. Law at either the Georgia Historical Society or the Beach Institute, but it costs money.

It is important to document Savannah’s black history for posterity, Jahannes says. “A number of people in various forms have gathered some measure of history, but the history of black Savannah has not really been told,” he says.

Easier access to black history

W.W. Law’s collection of documents and artifacts is massive, to say the least, but at some point, much of it will be available to historians and researchers.

Recently, the Georgia Historical Society announced it will be the repository for the collection.

“It’s basically everything Mr. Law owned at the time of his death,” says W. Todd Groce, president and CEO of the historical society. There are manuscripts, photographs and other paper documents and also artwork. There are phonographic records, there are books.

“We’re looking forward to the opportunity to processing that collection and making it accessible for research,” Groce says. “We don’t really know the extent of the collection, so one of the first things, we’ll have to survey and do a complete inventory and then determine how to process the collection.”

The process is expected to take at least three years before the collection is ready for public display. Once completed, it will represent the largest single collection of black history within the historical society.

The GHS was well-known to Law.

“He was up here frequently, doing research,” Groce says. “He came to our programs, and was a member and supporter.”

The collection will be an invaluable asset to historians.

“It’s important because of Mr. Law and the story of his life, not only as a civil rights worker, but also as a historian and leader of the African-American community,” Groce says.

“He was a promoter of Savannah, he loved Savannah. He did extensive work in trying to bring forward African-American history and promoting it.”

The collection also documents the larger story of civil rights in the United States, Groce says.

“He’s a national figure. You could pick up any book about the civil rights movement in Georgia and he plays a very prominent role.”

By making the collection accessible to students, teachers and researchers, a new generation will learn Law’s story, Groce says.

“It’s not just about African Americans, it’s American history,” he says. “It affects all Savannah, all Georgia, all Americans.

“We are a national research center. Last year alone, 50,000 people used the collection of the historical society.

“Those people came from around the world, from 43 different states, every county in Georgia and 11 foreign countries,” Groce says. “What we’re doing here is making the history of this state accessible to the entire world.

“That’s what’s going to really serve W.W. Law’s legacy the best.”

http://savannahnow.com/accent/2013-09-14/local-authors-strive-document-savannahs-black-history#.UjZWn9LLo2d

No comments:

Post a Comment