Robert Pearce introduces one of the most important – and misunderstood – thinkers of the 19th century.

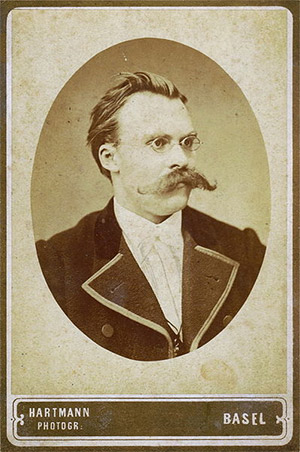

Nietzsche in 1872No one studying modern European history can avoid Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Events that marked and marred the modern world, including the First World War and the Nazi tyranny, and important social developments, like the secularisation of society, are closely associated with him. No philosopher, perhaps, has ever been considered so inseparable from politics, and few philosophers have ever influenced so profoundly the way people think about their lives. Many of his phrases – ‘the superman’, ‘the will to power’, ‘God is dead’, ‘live dangerously’, ‘blond beast’ – have become part of the currency of educated people’s language. According to J.P. Stern, had Nietzsche not lived ‘the life of modern Europe would be different’. Yet many of us know very little about the substance of this enigmatic figure – who once said we should philosophise with a hammer and write books in blood.

Nietzsche in 1872No one studying modern European history can avoid Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Events that marked and marred the modern world, including the First World War and the Nazi tyranny, and important social developments, like the secularisation of society, are closely associated with him. No philosopher, perhaps, has ever been considered so inseparable from politics, and few philosophers have ever influenced so profoundly the way people think about their lives. Many of his phrases – ‘the superman’, ‘the will to power’, ‘God is dead’, ‘live dangerously’, ‘blond beast’ – have become part of the currency of educated people’s language. According to J.P. Stern, had Nietzsche not lived ‘the life of modern Europe would be different’. Yet many of us know very little about the substance of this enigmatic figure – who once said we should philosophise with a hammer and write books in blood.

Was Nietzsche really a warmonger whose militarism caused war to break out in people’s minds even before the physical battles were joined in August 1914? What of his influence on Hitler and the Nazis? In a popular book, Fascism for Beginners, Nietzsche is described as an ‘ultraconservative’ thinker; and we see spouting from the mouth of a cartoon of this unmistakable, walrus-moustached figure the words: ‘Our ideal is to achieve the superman by collective experiments in discipline and breeding’. There is clearly a real danger that we may accept half-baked, even preposterous, notions about Nietzsche’s ideas and their influence.

The Man and his Work

Nietzsche certainly came from a conservative family. He was born in 1844 at Röcken, near Leipzig, in rural Prussian Saxony, the son of a Lutheran pastor. Indeed both his grandfathers were Lutheran ministers. His father, a convinced royalist who was proud of having once tutored royal princes, called him Friedrich Wilhelm after the King of Prussia, whose birthday, 15 October, he shared. Inevitably, this background of religion and support for state power marked the young boy.

Nietzsche stood out first because of his educational success. After his father’s death in 1849 (from what was diagnosed as ‘softening of the brain’), he was educated in Naumburg, at the prestigious Pforta boarding school and at the universities of Bonn and Leipzig. Then, at the remarkably early age of 24, he became Professor of Philology (specialising in classical Greek language and culture) at the University of Basel in Switzerland. Secondly, he stood out because he was anything but conventional.

Nietzsche tried very hard to be normal. At Bonn he did all that could reasonably be expected of a typical student, including boozing, duelling and whoring. He duly took part in long beery drinking bouts, and suffered the consequences without complaint. He acquired the obligatory duelling scar to his face, though apparently without the skill to inflict the same mark of honour on his opponent. If he turned tail and ran away from his first brothel, it seems that he returned (and, so most biographers suspect, contracted the syphilis which eventually killed him). But in the end he admitted that it was all too much. ‘Become who you are’, he was soon to advise: in other words, have the courage to rebel against the pressures that seek to mould and limit you – instead, find your true self.

Nietzsche was no ultraconservative but a rebel. ‘Strife is the perpetual food of the soul’, he had written as early as 1862. His own strife would not be in the realm of action. He had suffered migraine headaches and poor eyesight from early years, and though he volunteered to serve as a nursing orderly in the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, he soon collapsed from dysentery and diphtheria. He was never really well again. Instead, he would do battle in the realm of ideas. In particular, having lost his faith, he would take on religion. ‘If you wish to strive for peace of soul and happiness, then believe,’ he wrote to his sister; ‘if you wish to be a disciple of truth, then inquire.’ His own inquires led him to conclude that if God did not exist then there disappeared also the supposedly God-given values of right and wrong, good and evil. The death of God was the end of all absolutes; it created a total vacuum, a terrifying void. There was no meaning in life.

In 1879 Nietzsche’s health was so poor that he retired on a small pension from Basel University. He began travelling – to Germany, Switzerland, Italy, France – living in hotel rooms and unpretentious lodgings, incessantly writing and working out his answers to the philosophical questions that obsessed him.

Before this time, experts have noted several key influences on him. These included those Greek philosophers, especially Heraclitus, who stressed competition and emotion rather than mere logic; materialist thinkers, who denied the existence of anything metaphysical (including a self separate from the body); and also Darwin and other evolutionists, who saw no reason to presuppose the existence of a creator. The modern philosopher who impressed him most was Schopenhauer, partly because of his pessimistic outlook on life. It’s best to envisage the world as a sort of penal colony, insisted Schopenhauer: after all, life is ‘a disappointment and a cheat’ (words he wrote in English), death a welcome oblivion. ‘No rose without a thorn,’ he quipped, ‘but many a thorn without a rose.’ Such views must have had emotional appeal to a man who suffered as intensely as Nietzsche. But in fact what he took from Schopenhauer was a reverence for literary style, the idea of the ‘will’ as a force that made the world go round, and a belief that man simply cannot live by pessimism alone. The other major influence was Wagner, whom Nietzsche met in Switzerland. ‘When I am near him,’ he wrote in August 1869, ‘I feel as if I am near the divine.’ The two men soon quarrelled, but what the younger man took from his encounter with Wagner and his music was the notion of the hero.

In the years of his wandering, from 1879 to 1889, Nietzsche combined these separate influences into a philosophy that many judge to be revolutionary – and distinctly odd.

Nietzsche’s Philosophy

On 3 January 1889, in Turin, Friedrich Nietzsche saw a cabman beating his horse. He ran to the animal and threw his arms round the beast. Then he fell to the floor. When he retained consciousness, he was no longer sane. Almost his first act was to declare war on Bismarck and Wilhelm II of Germany. Soon he was to be observed naked, gyrating wildly in front of a mirror. It seems that syphilis had finally undermined his wits. For the last 11 years of his life, from the age of 44, he was looked after by his mother and then his sister, Elizabeth, as an alternative to entering an asylum. For the last two years he could not speak. He died on 25 August 1900.

Yet even before 1889 there were signs that Nietzsche was becoming unbalanced. His short autobiography Ecce Home (‘Behold the man’, words used by Pilate about Christ), published in 1888, contains chapters with the titles ‘Why I am so wise’, ‘Why I am so clever’, ‘Why I write such excellent books’, ‘Why I am a destiny’. The problems of getting to the heart of the man’s philosophy are compounded by the fact that his sister edited his surviving notes, containing ideas he’d rejected, into an often misleading work, The Will to Power, published the year after his death. Furthermore, in his prime, Nietzsche sometimes wrote in poems, parables, aphorisms, riddles and metaphors which are often difficult to fathom. (What actually did he mean when he wrote of ‘the splendorous blond beast, avidly rampant for plunder and victory’, and how do his wildly violent images square with his calls for compassion, as in ‘He who feeds the hungry refreshes his own soul: thus speaks wisdom’?)

Nevertheless, at the heart of Nietzsche’s philosophy is undoubtedly the notion that ‘God is dead’ and the consequent gaping hole in human existence. He spent a good deal of time criticising Christianity, which in his view at no point came into contact with reality. (The only words of the New Testament of which he approved were Pilate’s ‘What is truth?’. Faith, according to Nietzsche, means not wanting to know what is true.) Liberal thinkers believed the absence of a creator would not affect morality, but with this he profoundly disagreed. Sin was simply an invention of the priests. Conventional morality was no more than a custom. There were no God-given values; therefore there could only be man-made ones.

Man was at the centre of Nietzsche’s thought, but too many people lived inauthentic lives – they were ‘human, all too human’ (meaning weak, cowardly, self-deceptive, petty, selfish, lazy, small-minded, ignorant, dishonest, malicious, pathetic). But there was no set human nature, and therefore human beings could evolve. The means of this improvement was the will. The will was not so much free or unfree, as many philosophers had insisted, it was weak or strong, and if weak could become strong by overcoming obstacles and difficulties. Nietzsche believed that we must have a purpose in life (‘Man should sooner have the void for his purpose than be void of purpose’; if we have our why we can put up with any how). There was no set purpose, and therefore we had to devise our own. His own purpose was this quest to develop the will, and thus overcome littleness and futility. Life can become heroic if we are willing to give up ‘miserable ease’ and overcome our all too human weaknesses.

The man of strong will and clear sight was the Übermensch (literally the ‘Overman’, the man who has overcome himself, often rendered as the ‘Superman’). Such a one was almost a god. Certainly he defined good and evil. ‘What is good? All that heightens the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man. What is bad? All that proceeds from weakness.’ This was Nietzsche’s ‘transvaluation of values’.

Perhaps Nietzsche had to cultivate heroic will-power in order to avoid succumbing completely to ill health. In January 1880 he was suffering a ‘semi-paralysis which makes it hard for me to talk’ and also ‘furious attacks’ which had him vomiting for three days and nights at a stretch. He had so many problems in his life that he had somehow to turn all this ‘muck into gold’, or go under. He succeeded for a long time, and the hero of his great book of 1885, Zarathustra, affirms life nobly, joyfully and sometimes even ecstatically, despite all its problems and disappointments. Nietzsche was somehow able to accept his lonely, painful life and even to judge that if everything were repeated endlessly (as at times he thought it would be – the idea of ‘eternal recurrence’, one of his most curious late ideas) it would still be worthwhile.

Perhaps Nietzsche had to cultivate heroic will-power in order to avoid succumbing completely to ill health. In January 1880 he was suffering a ‘semi-paralysis which makes it hard for me to talk’ and also ‘furious attacks’ which had him vomiting for three days and nights at a stretch. He had so many problems in his life that he had somehow to turn all this ‘muck into gold’, or go under. He succeeded for a long time, and the hero of his great book of 1885, Zarathustra, affirms life nobly, joyfully and sometimes even ecstatically, despite all its problems and disappointments. Nietzsche was somehow able to accept his lonely, painful life and even to judge that if everything were repeated endlessly (as at times he thought it would be – the idea of ‘eternal recurrence’, one of his most curious late ideas) it would still be worthwhile.

Many have said that by the mid-1880s, Nietzsche’s outlook was almost theological, though he had replaced God with the Superman, divine grace by will-power, and eternal life with eternal recurrence. But he remained an individualist (a man who suffered, as he often said, not from solitude but from the multitude). It is important to realise that he redefined values for himself, not for anyone else:

This is my taste: not good taste, not bad taste, but my taste, which I no longer conceal and of which I am no longer ashamed …

‘This is my way: where is yours?’ Thus I answered those who asked me ‘the way’. For the way does not exist. Thus spoke Zarathustra.

Values were relative, not absolute. There is nothing either good or bad, Nietzsche implied, but willing makes it so. Every human being is a ‘unique wonder’, he insisted, challenging us to define our own values and forge our own purpose, and thereby give meaning to life.

Influence Assessed

William Shirer tells us that Nietzsche was a ‘megalomaniacal genius’, and Arno Mayer insists that his vision was as much political as cultural. Certainly it’s a commonplace that he contributed strongly to the climate of warlike ideas that helped produce war in 1914. ‘You should love peace as a means of new wars,’ he wrote; ‘and the short peace more than the long … I do not exhort you to peace but to victory.’ His books became bestsellers after his death. Thus Spoke Zarathustra alone sold 140,000 copies in 1917, and the man who fired the first shot in the war, the assassin Gavrilo Princip, admired Nietzsche and was given to quoting his works, especially the line: ‘Insatiable as flame, I burn and consume myself’.

Yet we must never forget that Nietzsche hated the militarism that followed the unification of Germany in 1871. The new Reich, he said, is the ‘politicisation and thus destruction of the true German spirit’, which to his mind was cultural. He wrote in February 1887 that ‘I have no respect left for present-day Germany, bristling, hedgehog-fashion, with arms. It represents the most stupid, the most depraved, the most mendacious form of the German spirit that ever was’. Small wonder, then, that he claimed Polish ancestry for himself, called himself a ‘good European’ rather than a German, and wished he could write in French rather than his native tongue. He also scorned the nationalistic Teutonic myths that so entranced Wagner. When Nietzsche had talked of waging war, he had in fact meant fighting against one’s own weaknesses, self-deceptions and follies. He did not expect to be taken literally, and probably only a society already deeply imbued with militarism would have interpreted him in such a way. If thinkers are to be held responsible for glorifying war and creating a militaristic atmosphere, then those figures – from John Ruskin to Max Weber – who glorified real war must be indicted before Nietzsche.

Nietzsche’s views were not ‘militarism run mad’ (which Colonel House believed had caused the First World War), they were individualism run mad. (Thus they appeal especially to those – including, in the past, students – who are relatively free of social obligations, dependants or debts.) Not surprisingly, therefore, he decided that liberalism was a product of the ‘herd mentality’. He cast scorn on the ‘non-sense of numbers’ and the ‘superstition of majorities’. (Utilitarianism, the doctrine that vaunted the greatest good of the greatest number, regardless of the needs of the individual, was merely ‘pig philosophy’.) To this extent, it may be said that he helped undermine the whole concept of democracy, which was very much a fragile plant in Germany in his day and later. Yet his individualism – which in political terms equates with anarchism – would have been even more opposed to the far greater collectivised tyranny of totalitarianism. Nevertheless both Mussolini and Hitler admired him.

In the early years of the twentieth century Benito Mussolini took as his motto the words ‘live dangerously’, which Nietzsche recommended to those who wished to live fruitfully and intensely. Mussolini believed that, as a determinist thinker, Marx needed a dash of Nietzschean free spirits. Hitler too was impressed. He read him as a prisoner in Landsberg (‘my university’), or so he said, and later gave Mussolini a copy of the collected works for his sixtieth birthday. In 1934 Hitler travelled to Weimar to pay his respects to Nietzsche’s sister, Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche, presenting her with a huge bouquet of flowers and speaking of his ‘unchanging reverence’ for her ‘estimable brother’. How can we account for the admiration of Mussolini and Hitler, unless Nietzsche were indeed a forerunner of fascism?

There are several explanations. The first is that a little learning is a dangerous thing. Certainly it seems very unlikely that Hitler knew more of Nietzsche than a few slogans. Secondly, the version of Nietzsche of which many fascists approved was that painted by his sister in The Will to Power. Elizabeth evidently did have extreme nationalist, racist and fascist sympathies, and her husband more so. Third, we should never underestimate the capacity of people to see what they want to see, especially in the enigmatic works of poets or philosophers.

But it is also true that Nietzsche had waged war on traditional thinking; he had encouraged people to choose their own goal and their own morality; and he had also shown lofty contempt for the masses. Could he complain if certain individuals chose mass murder as the meaning of life? According to Stern, Nietzsche was a naive ‘accomplice’ of the Nazis and Adolf Hitler came closer than anyone else to doing what Nietzsche admired – creating his own values and embodying ‘the will to power’.

Few would deny that Nietzsche, in attacking traditional morality, had unknowingly played some small part in the origins of fascism in Europe. Yet freedom was the essence of his philosophy – and this, as George Bernard Shaw, a Nietzschean thinker, once wrote, ‘means responsibility’. (He added, perceptively, ‘That is why most men dread it’.) Certainly the perpetrators of Nazi atrocities could not call Nietzsche to their defence. Had Hitler been a true disciple, there would surely have been no war, no breeding experiments and no holocaust. He would have overcome his ‘all too human’ rancour, his pettiness, his muddled thinking, his unwillingness ever to question his own assumptions, his lack of self-knowledge and need for scapegoats.

In addition, Nietzsche can bear no blame for the racism which many historians see as constituting the essence of Nazism. The philosopher strongly criticised the anti-Semitism of Wagner. Anti-Semites, he said, were Schlechtweggekommene – losers and misfits, members of the ‘herd’, envious creatures who simply wanted scapegoats to excuse their own failures. He disliked their religion, as he disliked all religion, but said he’d welcome the Jews’ involvement in ‘the strongest possible European mixed race’, for such impure races were typically ‘the source of great cultures’. Clearly the fascists had read too little Nietzsche not too much.

Friedrich Nietzsche, an atheist, was buried in the churchyard at Röcken, next to his father, after a Lutheran ceremony. His surviving family took no account of his wishes. Neither did the Nazis, who hijacked him. Those who insist that he is a progenitor of the fascists, while they sometimes take note of the letter of his work, patently ignore its spirit.

Issues to Debate:

- What are the central ideas of Nietzsche’s philosophy?

- How new was his thinking?

- To what degree should Nietzsche be held responsible for the First World War and for Nazi policies?

Further Reading:

- Curtis Cate, Friedrich Nietzsche (Hutchinson, 2003)

- Ronald Hayman, Nietzsche: A Critical Life (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980)

- R.J. Hollingdale, Nietzsche: the man and his philosophy (CUP, 2001)

- Stuart Hood and Litza Jansz, Fascism for Beginners (Icon Books, 1993)

- Arno J. Mayer, The Persistence of the Old Regime (Croom Helm, 1981)

- J.P. Stern, Nietzsche (Fontana, 1978)

- Rüdiger Safranski, Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography (Granta, 2003)

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Secker & Warburg, 1957)

- Albert Speer, Spandau: The Secret Diaries (Collins, 1976)

No comments:

Post a Comment