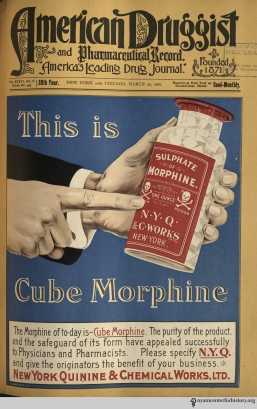

By 1900, use of narcotics was at its peak for both medical and non-medical purposes. Advertisements promoting opium- and cocaine-laden drugs saturated the newspapers; morphine seemed more easily obtainable than alcohol; and widespread sale of drugs and drug paraphernalia gained the attention of medical professionals and private citizens alike.1 State regulations failed to effectively curb distribution.

December 17, 1914, Congress approved the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act. The Act’s passage critically impacted drug policy for the remainder of the century, and the habits of physicians with regard to prescribing and dispensing medicine. read on ...

On the one hand, the medical establishment held that addiction was a disease and that addicts were patients to whom drugs could be prescribed to alleviate the distress of withdrawal. On the other hand, the Treasury Department interpreted the Harrison Act to mean that a doctor's prescription for an addict was unlawful. The United States Supreme Court quickly laid the controversy to rest. In Webb v. U.S., 249 U.S. 96 (1919), the Court held that it was not legal for a physician to prescribe narcotic drugs to an addict-patient for the purpose of maintaining his or her use and comfort. U.S. v. Behrman, 258 U.S. 280 (1922), went one step further by declaring that a narcotic prescription for an addict was unlawful, even if the drugs were prescribed as part of a "cure program." The impact of these decisions combined to make it almost impossible for addicts to obtain drugs legally. In 1925 the Supreme Court emphatically reversed itself in Linder v. U.S., 268 U.S. 5 (1925), disavowing the Behrmanopinion and holding that addicts were entitled to medical care like other patients, but the ruling had almost no effect. By that time, physicians were unwilling to treat addicts under any circumstances, and well-developed illegal drug markets were catering to the needs of the addict population. Read more: here ...

WOMEN AND DRUGS: 1850-1914 .... As early as 1782, it was

common practice for women of Nantucket Island to take “a dose of

opium every morning” (De Crevecoeur 1981). Anecdotal evidence

of increasing use of opium by women was provided by writers such as

Baltimore physician A.T. Schertzer (1870) and Massachusetts surveyist

F.E. Oliver (1872, pp. 162-177), who quoted a physician who said, “The

use of opium has greatly increased, especially among women.” Dr. J.B.

Mattison (1879a), who wrote and lectured extensively about drug use in

the United States, expressed his concern about laudanum addiction: “How

many women are to-day sitting in a similar shadow is beyond our

knowing; but it is known that they swell largely the ranks of opium

habitués. . . . My personal experience is entirely confirmatory of this

statement.”

The use of opiates by Victorian women, especially upper-class

women, was generally accepted by society and their physicians. In 1871

one physician specifically found that opiate addiction “among women

in high places is incredibly large” (Calkins 1871, p. 165). In 1867 Ludlow called attention to

the increase in opiate use among “our weary sewing-women” (Ludlow

1867, pp. 377-387; Day 1868, p. 283), and Day (1868, p. 7) listed

“women obliged by their necessities to work beyond their strengths” as

heavy opiate users. read on ...

No comments:

Post a Comment