Right now, all across the country, people are having sex, just for the fun of it. Yet despite centuries of birth control designed to maximize pleasure and minimize risk, we still can’t admit this basic truth.

Maybe that’s because contraceptives are such a messy subject: Throughout history, people have used everything from seaweed to sheep intestines in order to prevent pregnancy, when all they really wanted to do was get laid. In the United States, it wasn’t until World War II that condoms were finally embraced as the pleasure devices they really are. Thanks to Uncle Sam, American troops were given condoms to keep them healthy while enjoying the action overseas, so to speak.

By the end of the 1940s, the condom had outlasted an act of Congress, which reinforced social stigmas and drove users to the black market, to become the safe-sex staple, the king of the contraceptive industry. And yet its packaging remained opaque, its purpose shrouded in secrecy, a product whose intended use was only indirectly suggested. So how did the condom go from contraband to federally issued necessity without anyone ever talking about sex?

The answer lies in the history of birth control itself, which has existed at least since the Egyptian era, when people created their own barrier methods or suppository mixtures made of natural elements like honey or seaweed. Sarah Forbes, curator at the Museum of Sex, explains that over the years, “you have people making condoms out of linen sheets, you have people making them out of fish-bladders and animal intestines.” As new materials were introduced, people invariably made condoms out of them.

In the early 18th century, when slaughterhouses discarded an abundance of animal organs, butchers made extra money by repurposing intestines as preventive sheaths, making them the first widely sold contraceptive product. Since the livestock industry was much larger in Europe, most of these “skins,” as they were called, had to be imported from England or France. Long before the advent of the birth control pill, these condoms became the most effective, affordable, and accessible form of contraception.

“Condoms were sold as sheaths, skins, shields, capotes, and ‘rubber goods’ for ‘gents.’”Condom production ballooned after 1839, when Charles Goodyear’s method of rubber vulcanization kick-started modern latex technologies in the United States. By 1870, condoms were available through almost any outlet you can imagine–drug suppliers, doctors, pharmacies, dry-goods retailers and mail-order houses. It may seem suprising today, but sexual products were openly sold and distributed during much of the 19th century. Then, suddenly, in 1873 Congress passed the Comstock Act, which paralyzed the growing industry; Comstock made it illegal to send any “article of an immoral nature, or any drug or medicine, or any article whatever for the prevention of conception” through the mail.

Packing Your Prophylactic: Before the term became exclusively used for condoms, toothbrushes were often advertised as prophylactics.

Jim Edmonson, chief curator at the Dittrick Medical History Center, explains that the law was passed primarily because of a vicious campaign by its namesake, Anthony Comstock. “He was a do-gooder, a reformer, and a religious-minded person,” says Edmonson. “Comstock had been to the Civil War, and was outraged by the sexual excess of soldiers–large numbers of men away from home and church–and the women who made their trade with these soldiers. Comstock felt that condoms and any other forms of contraception were just a license to sexual excess.”

Ostensibly designed to prevent the sale of obscene literature and pornography, the Comstock Act effectively made any form of contraception illegal in the United States, punishable as a misdemeanor with a six-month minimum prison sentence. “So we had a national law criminalizing contraception,” says Edmonson. “It’s hard to believe, but it’s true.”

Comstock’s crusade was aimed at commercialized vice, visible in the red-light districts, erotic paraphernalia, and birth-control products easily accessed in cities like New York during the 1860s. Fearing the widespread corruption of young uneducated minds, Comstock particularly sought to reform salacious newspaper advertising and the illicit mail-order marketplace it supported.

In a time before chain stores and online shopping, mail-order catalogs were all the rage, allowing millions of folks scattered across the countryside to purchase items made in urban areas, like condoms. Though the Comstock Act added to pre-existing regulation of “obscene” mail, it effectively closed certain loopholes and incorporated almost any product you can imagine. Contraceptives were one of the new additions.

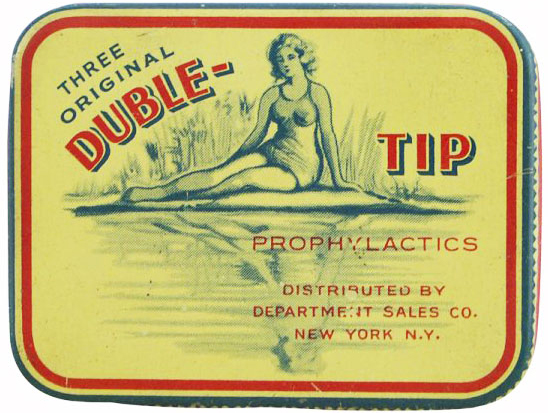

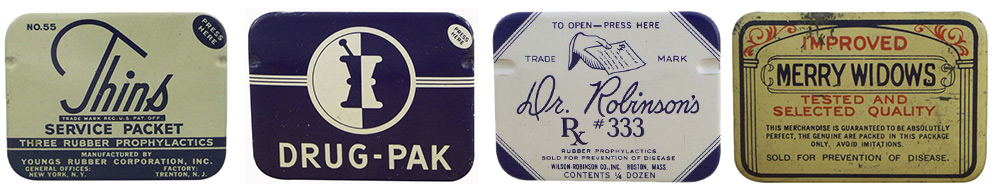

Three early condom tins rely on subtle cues to convey their contents’ usage. Courtesy Dittrick Medical History Center, CWRU.

Carol Queen, staff sexologist and curator at Good Vibrations’ Antique Vibrator Museum, agrees that Comstock devastated the burgeoning condom industry. “Not only was this happening at a moment in time when people were not speaking very overtly about sexuality, but it created this additional level of legal and moral persecution,” says Queen.

As a result, condoms went underground. In her book “Devices and Desires,” Andrea Tone observes that instead of ceasing production, “purveyors disguised their products through creative relabeling.” Tone points out that despite the legal issues, “Classified ads published in the medical, rubber, and toilet goods sections of dailies and weeklies indicate a flourishing contraceptive trade in post-1873 America. The hitch was that contraceptives were rarely advertised openly as preventives.” Instead condoms were sold as sheaths, skins, shields, capotes, and “rubber goods” for “gents.”

“Nearly 18,000 soldiers a day were unable to report for duty because of sexually transmitted infections.”Though Comstock pursued those on both the manufacturing and distribution ends of the contraceptive trade, smart entrepreneurs realized they were safe if the court had no clear evidence of their intention to prevent pregnancy. Although the transmission of venereal disease (VD) was not completely understood, germ theory was beginning to take root in the scientific community, so emphasizing this other medical use for birth-control products gave the industry good cover. Tip-toeing around the topic of contraception, ads relied on words like “protection,” “security,” and “safety,” phrases which Andrea Tone calls “legal euphemisms.”

Up through the 1920s, publicizing condom sales was off-limits for rubber-industry leaders, so individual entrepreneurs stepped in to make a dollar. Small businesses with diverse product lines could better hide from federal prosecution, resulting in a proliferation of mom-and-pop condom companies during the late 19th century.

Four condom tins from the 1930s highlight fantasies of the Mid-East with names like Sheik, Ramses, and Sphinx.

Julius Schmid (born Schmidt) operated one of these early start-ups. While working in a sausage-casing firm in New York, Schmid launched a more lucrative side business selling “skins” made from surplus animal intestines. A police raid on Schmid’s home barely slowed him down, and by the 1920s, Schmid was one of the largest condom producers in America. Despite this booming black market, condoms were impossible to advertise openly since they served no other known purpose aside from contraception. It wasn’t until America entered World War I in 1917 that the health hazards of unprotected sex became obvious.

The U.S. military knew it had a problem on its hands even earlier. In 1905, in an effort to combat common infections like gonorrhea and syphilis, the Navy implemented the first trial system of chemical prophylaxis dispensed by staff doctors. Though the treatment was strictly post-intercourse, its results impressed Navy brass enough that the procedure became standard on all ships by 1909. However, one of the system’s major flaws was its dependence on self-reporting to a doctor, so the following year prophylactic kits or “pro-kits,” were distributed to soldiers for self administration. This was highly preferred to an exam, and though still painful, the pro-kits protected many recruits from being court martialed for contracting VD.

The Dough Boy Prophylactic kit was first distributed by the U.S. military in 1910, and contained a painful ointment to be applied post-intercourse.

When draft examinations for World War I revealed infections for nearly a quarter of all recruits, military policy was altered to accept some soldiers with pre-existing VD. Over the next two years, around 380,000 American soldiers would be diagnosed with some form of VD, eventually costing the U.S. more than $50 million in treatment. Jim Edmonson explains that during World War I, American soldiers weren’t issued condoms; instead they were given a “Dough Boy Prophylactic Kit.” The idea behind these kits was that soldiers who “went out on a weekend furlough and had sexual contact would then clean themselves up afterwards with antiseptics and urethral syringes and so forth.” Edmonson points out that this method was like “closing the gate after the horse is out of the barn; not very effective.”

This U.S. military poster from World War II urged soldiers to use pro-kits after sex to stop the spread of VD.

This half-hearted prevention program resulted in a complete epidemic of sexually transmitted infections. Sarah Forbes says nearly 18,000 soldiers a day were unable to report for duty because of these illnesses. Starting with the pro-kit, which Forbes describes as “glorified soap that was completely ineffective,” the U.S. military began its attempts to counteract the dire consequences of VD. Slowly but surely, they provided condoms and developed health education programs, which Forbes says became the precursor to sex-education in American public schools.

As Andrea Tone observes, “The VD crisis freed Americans to reclassify sex as a legitimate subject of scientific and social research and made sexual behavior a matter of public welfare.” In 1918, Congress created the Division of Venereal Diseases as a part of the U.S. Public Health Service, allocating more than $4 million for prevention and treatment. That same year, the Crane-Chase court ruling legalized physician prescribed birth control for the “cure and prevention of disease,” clearing the way for unfettered condom distribution. After decades of secrecy, this decision gave sexual products a public reprieve, though Jim Edmonson points out that their contraceptive uses were notably unmentioned. “That was implicit, understood, and implied, but not overtly stated,” says Edmonson, “So ‘wink-wink.’”

Though the U.S. was the only Allied force that didn’t distribute condoms to its soldiers during World War I, American recruits learned of condoms from their compatriots, and brought that knowledge (and their consumer dollars) home with them following the war. Simultaneously, American condom manufacturers established a major industry foothold by supplying European militaries with the condoms they badly needed.

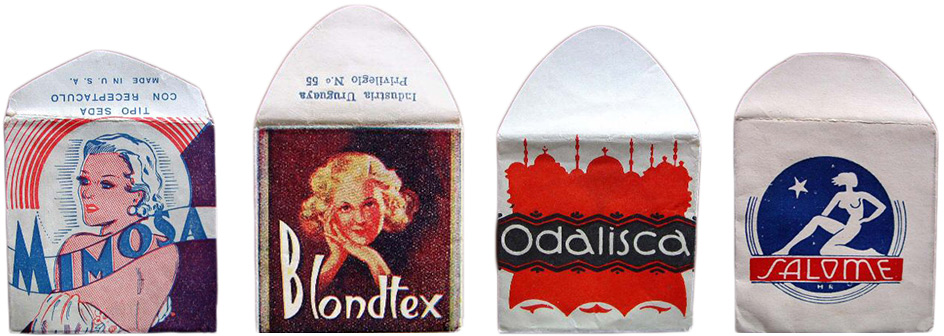

The proliferation of condoms was immediate, though their marketing still required a certain amount of decoding. “Prophylactic,” which had been used to sell benign health-related products like toothbrushes, was quickly co-opted as the industry term for condom. Many manufacturers implied doctor endorsement with phrases like “scientifically tested on modern equipment for your protection” or “exclusively a drugstore item.” Mid-century condom packaging from the Kinsey Institute Collection includes coded taglines like, “the perfect hygienic rubber product” and “a product of genuine latex sold for prevention of disease only.”

Though this clinical language put condoms at the far end of the spectrum from sexual pleasure, product packaging implied sex in other ways. Carol Queen says, “What’s interesting about that moment historically, as far as ads for any product that had a sexual purpose, is that there’s a cryptic language being used that made people think about the real function without ever actually saying it.”

Subtle hints at the tawdry or dangerous worked well for condoms, with brands like Devil Skin, Shadows, and Salome hitting the shelves in the ’20s and ’30s. One popular label, Merry Widows, was named after a long-standing slang term for condoms that implied a certain illicit pleasure.

Subtle hints at the tawdry or dangerous worked well for condoms, with brands like Devil Skin, Shadows, and Salome hitting the shelves in the ’20s and ’30s. One popular label, Merry Widows, was named after a long-standing slang term for condoms that implied a certain illicit pleasure.Sarah Forbes describes early condom tins as very ornate, hinting at a kind of decadence as well as “masculinity, strength, and endurance.” Many companies emphasized testosterone-fueled virility with names like Spartans, Buffalos, Stags, Pirates, Trojans, Romeos, or Knights. Other brands evoked an exotic, Far Eastern world of harems and belly-dancers that automatically triggered sex in many adult minds.

Finally, in 1937, the FDA instituted national standards for condom testing in order to fight venereal disease, which further legitimized the industry. This also meant that larger companies with more resources for quality control testing could succeed where small businesses couldn’t. Giants like Julius Schmid, who made Ramses and Sheiks, and Youngs Rubber, responsible for Trojans, came to dominate the U.S. market.

World War II era ads published by the military reminded men of the dangers a pretty face can hide; even Donald Duck was enlisted to publicize the need to use a “Pro.”

By the time the U.S. entered World War II, American soldiers were much better prepared for VD. The military stopped focusing only on prevention through abstinence and post-infection treatment, incorporating condoms on its approved list of prophylactics. Troops could purchase sets of three condoms for ten cents at “pro stations” placed for easy access, day or night. The military also created an aggressive advertising campaign promoting safe sex through prevention, combining images of sexy women with the not-so-sexy effects of VD.

Catherine Johnson-Roehr, curator at the Kinsey Institute, points to the normalization of condoms in a military travel guide to Brussels produced during World War II. In addition to famous attractions, churches, and dancehalls, the booklet includes a page titled “Pro Stations,” illustrated with a little devil character and listing the addresses for seven different prophylactic stations around Brussels. This kind of sanctioned condom distribution ultimately gave American businesses such a boost that condom production doubled between 1939 and 1946.

Although the trade was legitimized and regulated by the U.S. government, the taboo surrounding condoms hadn’t disappeared; in fact, condoms were still so stigmatized that even pharmacists were afraid to display them openly. Sarah Forbes says one of her favorite artifacts from the period is a wooden countertop display case designed to hold condoms. The cabinet was made with modesty doors to protect women and children from the scandalous condom tins it held, and when its doors are closed, all that’s really visible is a label at the top that says “Julius Schmid.”

This drugstore cabinet produced by Julius Schmid has privacy doors that could completely conceal its products. Courtesy the Museum of Sex.

While the spread of condom vending machines during the ’50s helped make them a recognizable part of the American consumer landscape, it wasn’t until the sexual revolution of the ’60s and ’70s that the topic was finally spoken about more openly, with humor and pleasure entering the conversation. But today, we still have difficulty speaking frankly about the nature of condoms. The language may have changed, but we’re still censoring our discussion of birth control. For example, instead of saying “prophylactic,” we use the phrase “preventive care.”

Sarah Forbes says that while the condom’s contraceptive purpose doesn’t faze most people, condoning their use merely for pleasurable reasons is still controversial. Forbes recalls that “just a couple of years ago we had Trojan ads that could only be shown on TV at certain times of night on certain networks.” Both CBS and Fox declined to run the commercials, simply because they didn’t focus on the condom’s role in disease prevention. As Fox explained to Trojan, in language harking back to 1918, “Contraceptive advertising must stress health-related uses rather than the prevention of pregnancy.” Here we go again

No comments:

Post a Comment