As we reflect on Pearl Harbor Day, here’s something to keep in mind: The “men” who fought and died for the United States in World War II, were just barely out of adolescence, as young as 18 years old—the same age as guys obsessed with “Maxim” and Grand Theft Auto today. The WWII flight jackets painted with provocative pin-up girls, favorite comic characters, or lucky charms are a reminder of just how young these servicemen were.

“If this guy wants to paint a naked lady on the back of the jacket, why stop him? He could be dead tomorrow.”At the beginning of the war, Army Air Corps members were issued the most badass jacket in the military, the leather A-2—which had been the standard leather flight jacket since 1931. In WWII, these jackets became a canvas for teenage flyers to express their rugged individuality. They’d get the backs painted, and often these images included the plane’s nickname and little bombs to tally how many missions the crew flew. On the front, personalized patches would often indicate one’s squadron or bomb group.

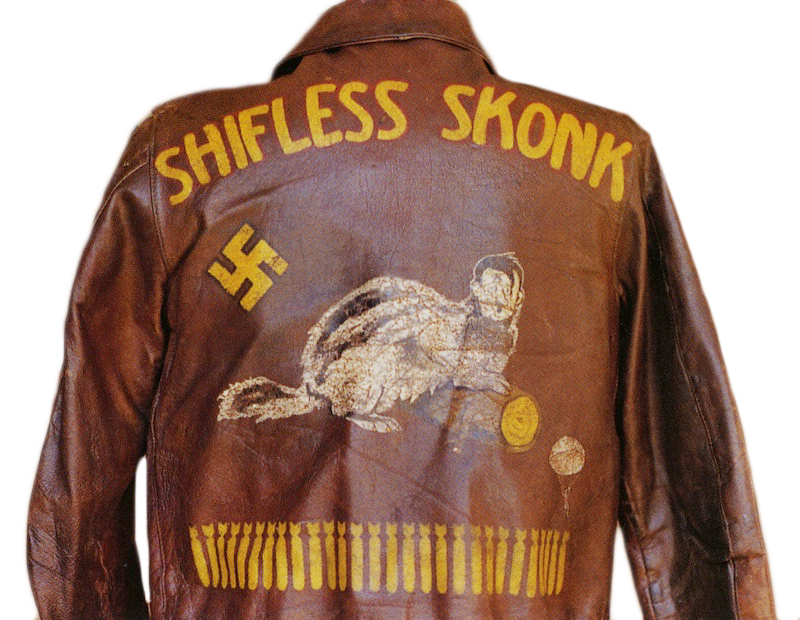

On the bawdiest of these jackets, scantily clad babes gleefully ride phallic bombs. On others, cuddly cartoon characters charge forward, bombs in tow, driven by a testosterone-fueled determination to kill. Some jackets depict caricatures of Native Americans or Pacific Islanders, usually drawn with bones in their noses. Even rarer are those showing Hitler being humiliated—while the number of bombs designated missions flown, swastikas represented German aircrafts destroyed.

Top: Staff Sgt. Cyril Dworak, an air gunner, had a fellow airman in the 96th Bomb Group, Joe Bodner, paint his jacket. The swastika denotes a victory over a German fighter plane. Above: Officers of the 23rd Fighter Group pose with their “Shark Mouth” P-40. From the collection of John Campbell.

“I’ve talked to people who, when they got back from the war, hung their jacket up in the closet because they wouldn’t dare ever wear it in public again,” says John Conway, co-author of Schiffer Books’ American Flight Jackets and Art of the Flight Jacket. “When you’re a teenager and you’re 3,000 miles from home, having a naked lady painted on the back of your jacket is not that big a deal. But you wouldn’t want your mom to see it.”

You might think the concept of personalization would be frowned on in the U.S. military. After all, aren’t soldiers stripped of their identities in boot camp, where they dress in uniform, fall in line, follow orders, and work as a cohesive unit? Conway’s co-author Jon Maguire says American soldiers have always held on to their individuality in some way.

“In the Revolutionary War, the soldiers would carve on their powder horn or take a nail and make a stipple design on their musket,” says Maguire, an Oklahoma City historian for World War II’s 27th Air Transport Group, in which his father served. “You saw the same thing in the Vietnam conflict nearly 200 years later. Infantrymen would take their helmets and decorate the camouflage covering with peace signs, playing cards, or rock bands, like Creedence Clearwater Revival or the Beatles, whatever they were into.”

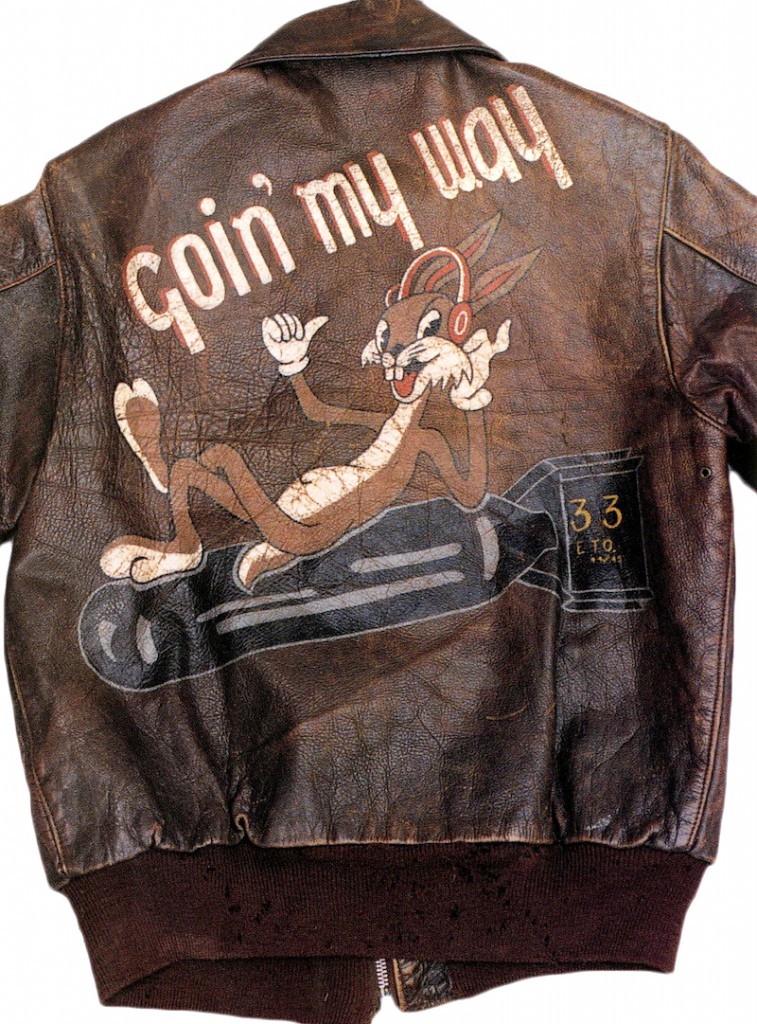

Pete, a pilot in the 100th Bomb Group, flew a B-17 bomber “Goin’ My Way” and had Bugs Bunny painted on his A-2 jacket. The bomb tail indicates he flew 33 mission. From the collection of Jeff Spielberg.

“World War II was a very different situation in which everybody enlisted,” Maguire says. “Right now, there’s a real small part of the population going into combat zone. Back then, they were only strict about the regulations that mattered, and it went from one commanding officer to another. Some of them were sticklers and some weren’t.”

During World War II, the Army Air Corps commanders may have had deeper reasons for turning a blind eye to jacket paintings, the same way they ignored the nose art that adorned airplanes with similar motifs.

Flight officer Robert J. Meer in Lipa, Philippines, with the “Glider Wolf” insignia of the 1st Glider Provisional Group painted on the front of his A-2.

“The flyers were allowed to go to town blowing off steam because they were dealing with death in a much more immediate sense than the infantry were,” says Conway, who’s worked at the militaria-focused Manion’s International Auction House in Kansas City, Kansas, for 33 years. “When you were up there in a plane, you’d get shot at, and you couldn’t call field artillery to support you. You had no ambulance, no medic. There was no tank to come in and run over the enemy. All it took was one accurate aircraft shot, and a plane full of 10 guys was gone.

“The commanders, for the most part, understood this,” Conway continues, “So there was a little bit more leniency in that regard than there would have been with ground guys. The officers figured, ‘Well, if this guy wants to paint a naked lady on the back of the jacket, what good is it to try to stop him? He could be dead tomorrow morning.’ The main objective was winning the war, not enforcing minor regulations and rules.”

During a time of peace, Maguire explains, the military goes by the book, but during a world war, the rulebook often goes out the window.

The B-17 known as “Lady Lorrie,” from the 306th Bomb Group, flew 35 missions, according to this jacket. The original owner is unknown. Via Manion’s International Auction House.

Bugs Bunny and other characters from Looney Tunes and Walt Disney cartoons were particularly popular motifs with young pilots, as were the Vargas Girls from Esquire magazine. (Disney artists, for what it’s worth, designed many of the squadron patches or insignias.) Conway says we have to remember that American pop culture was a lot smaller and a lot more homogenous at the time. No one had the Internet, cable, or even a TV. The A-2 and nose art imagery tended to come from radio programs, newspaper funny pages, comic books, magazines, and cartoon reels shown before movies, which served as a common language for young Americans.

Glider pilots Sam Altman, Frank Randall, and Troy Shaw of the 1st Air Command Group goof around for a photographer in India in 1944.

“Again, you’re talking about guys who were 18, 19 years old,” Conway says. “And this was the first place they’d ever been besides home. They tended to cling to things that were familiar to them. A lot of those guys read comic books and the comic strips in the newspapers when they were kids, and that stuff just stayed with them. They listened to popular radio shows like ‘The Lone Ranger’ and ‘The Shadow,’ and then they would visualize characters from those programs and paint them on the aircraft.

“So there might have been aircrafts with the same name in several different groups because this particular character or phrase was common knowledge to people in that age bracket,” he continues. “Our lives now are much more multidimensional than theirs were. Those guys might get to read the comic strip ‘Felix the Cat’ once a week while we can see an unlimited number of them at any time of the day.”

Some of the jackets are very individual, portraying iconography that’s personal to the soldier, such as his girlfriend’s name or the outline of his state. Others repeated phrases or symbols adopted by the group or squadron, like the nickname of their aircraft, which itself could be a play on the skipper’s name or the name of his wife or girlfriend.

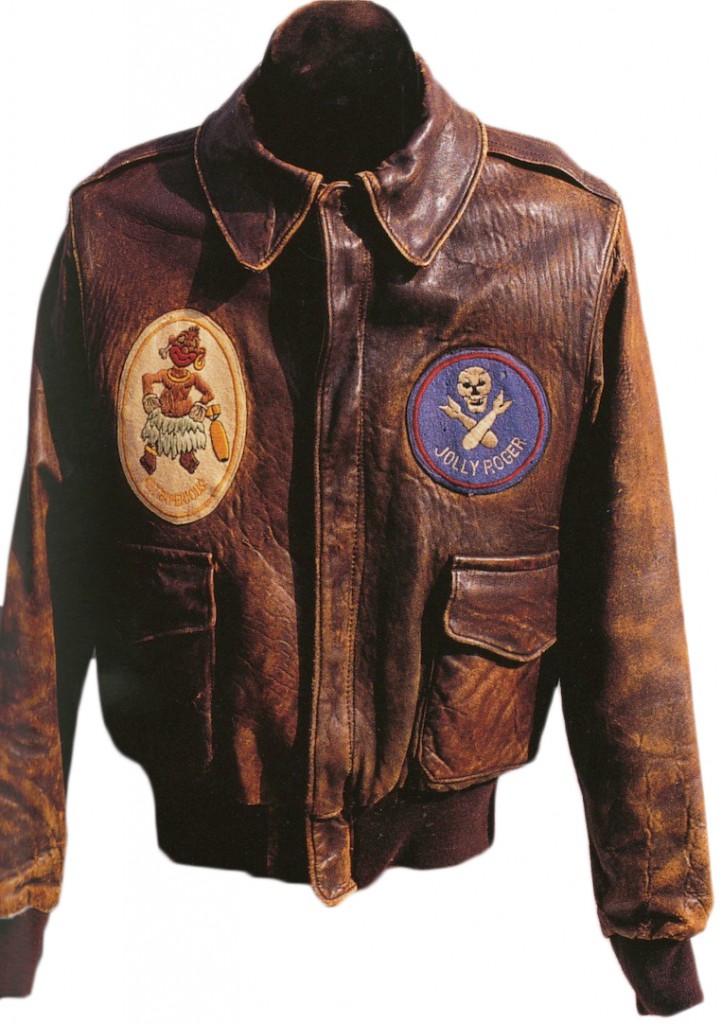

Lt. Ken Strong, who’d been an artist for Walt Disney, created the Pacific Islander character Asterperious for the 319th Bomb Squadron. The jolly roger with cross-bombs was the insignia for the 90th Bomb Group. From the collection of Jeff Spielberg.

Certain squadrons or groups adopted their own fighting philosophies, too. The 90th Bomb Group in the Pacific, for example, saw themselves as swashbuckling pirates, adopting the nickname Jolly Rogers. Their symbol became a skull with crossed bombs (as opposed to crossbones), an icon they embroidered into their unofficial squadron patches and sometimes painted on their jackets or planes.

While familiar cartoons or pretty ladies gave the soldiers a sense of comfort, menacing images such as pirate flags, grim reapers, or ferocious animals were intended to give them a sense of power and protection. (The earliest nose art were shark’s teeth, painted across the fuselage.) The same goes for lucky charms like dice, playing cards, and rabbit’s feet.

“So many of the guys were superstitious,” Conway says. “However, even though religion was much more prevalent in the day-to-day lives of those guys, you don’t often see religious imagery on flight jackets. I’ve often wondered about that.”

Airmen stationed in the Mediterranean would buy beautiful hand-tooled and hand-painted leather patches like this one made in Italy.

The quality of work you see on painted flight jackets ranges from the rough-hewn and child-like to the lush, textured work of master painters. Some airmen painted their jackets themselves, while some hired gifted European street artists, who turned this trend into a cottage industry. It’s likely that most flyers hired the guy in the squadron who knew how to paint.

“In the ’30s and ’40s, being a sign painter with some artistic skill was probably not all that unusual because every little American city and town needed somebody who could paint a sign,” Conway says. “They’re almost industrial-grade skills. Their work is very mono-dimensional and not too artistic in a technical sense but it got the job done.”

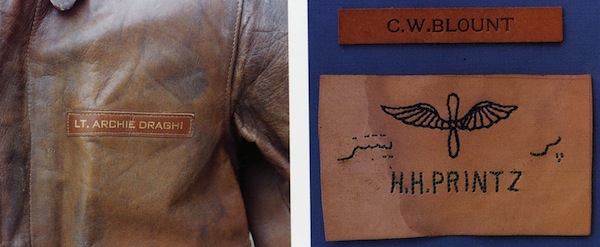

Left, this name tag for Lt. Archie Draghi, a group lead navigator for the 15th Air Force, used impressed gold leaf. Right, the issue name tag above, and a “private purchase” name tag below with the airman’s name in English and Farsi.

Painting the back of the jacket was just one way American pilots attempted to personalize the standard issue jackets. Some would buy fancy name tags to replace standard-issue leather name tags with block lettering. Others picked up little bells from a mission in San Michele, Isle of Capri, which would be hung from the collar hook as a good-luck talisman. Others put rabbit’s feet, dice, or bomb tags on their zipper pull.

Of course, the patches worn on the left or right breast of the jacket to indicate your allegiance to your squadron could be made of embroidered cloth or tooled, hand-painted Italian leather. These, too, shared the same sort of humor and imagination of the imagery on the jacket’s painted back.

Capt. Sam Trave, of the 347th Fighter Group, wears a silver “Good Luck” bell from San Michele, Isle of Capri, attached to the collar hook on his unusually dark A-2 jacket.

The U.S. Navy and Marines had pilots in their ranks, too, but painted leather jackets were never as widely accepted in those branches. The Navy leather flight jacket was the G-1, which had a lamb’s wool collar. These were more commonly decorated with clever patches mostly seen on the front of A-2s.

On A-2s from the China-Burma-India Theater, you’ll often come across silk banners known as “blood chits.” These had the occupied nation’s flag with messages on them in multiple languages intended to convey that a downed airman was not a threat, but someone who wanted to help them fight the Japanese. Usually, a reward was offered for helping the soldier get where he was going.

A hand-embroidered blood chit has a Republic of China flag and a Chinese message promising a reward to anyone who helped the airman get back to Allied lines.

“The blood chits were to protect people when they were in a situation where they didn’t speak the language in the locale,” Conway says. “They were originally an issue item with an ID number that was supposed to be associated with a specific individual, so the validity of the rescue could be verified. But then as the Army traveled all over Asia, it became the cottage industry for the people that lived in the countries they occupied. You see blood chits that were painted, embroidered, and printed from China, Burma, India, and some parts of the Pacific Islands.”

Some soldiers sewed the blood chit to the back of their A-2, until word got around that the flag could make an obvious target. The chits were also sewn inside the jacket, to make an internal pocket that could hold a survival kit or a cigarette case.

Glider pilot Nesbit L. Martin, from the 1st Air Commando, shows off his blood chits sewn inside his A-2.

Originally made of horsehide, the A-2s became standard issue in the Army Air Corps around 1931. At the time, leather jackets were popular with early aviators, who wore thick layers of clothing to protect them from the wind and cold of high altitudes.

“I’m interested in the individual soldier: What was it like to be there? What did it smell like and what did they eat? What did that person feel?”After the bombing of Pearl Harbor prompted America to enter the war, factories had to ramp up their production of A-2s, using goatskin and cowhide as well. But they still couldn’t keep up with the demand, as the number of pilots in training went from hundreds to tens of thousands. In April 1943, the Army declared the A-2 a “limited standard” and stopped ordering them, only issuing the jackets remaining in store.

The standard issue became the B-10 jacket, made of wool and water-resistant gabardine, while the A-2, was replaced with the less-popular leather AN-J-3, which was only produced in small numbers. But the A-2 jackets were considered so cool that new recruits would do whatever they could to get their hands on one.

The A-2 of Richard E. Fitzhugh, the pilot of the B-17G “El Lobo II,” who completed 30 missions with the 457th Bomb Group. Then in 1946, he flew Winston Churchill on a speaking tour, and “El Lobo II” became the subject of a model kit.

“My Dad went in ’44, and he still got an A-2,” Maguire says. “I’m sure some government stores had more than others. Guys would trade stuff all the time, too. The A-2s were pretty well sought after. You see paratroopers and tankers occasionally wearing them. A lot of fighter pilots wanted tanker jackets because they were actually warmer than the A-2. The tanker jackets had a wool blanket-type lining, and they weren’t as bulky in a pilot cockpit as Army’s cold-weather shearling-lined B-3 flight jacket, which was the alternative. So a lot of times pilots would try to trade tankers out of those. Transport guys would go into bases where they stored stuff, and they could commandeer stuff there—or beg, borrow, or steal whatever they were looking for. Soldiers were resourceful.”

Perhaps part of the appeal is the sense of swagger associated with the A-2. Young pilots in the 1930s and 1940s glorified the images of early aviators like Charles Lindbergh, who had a masculine flair with his iconic leather coat, riding breeches, and scarf.

“The A-2s are great—an American thing,” Maguire says. “Leather jackets were always popular in the civilian culture, too, with auto races and motorcycle riders. And the A-2s looked like biker jackets. One of the big movies when I grew up was The Great Escape, with Steve McQueen being chased by the Germans and jumping over barbed-wire fences with his motorcycle.”

Six U.S.O. Girls wear A-2 jackets belonging to the 90th Bomb Group, a.k.a. “Jolly Rogers,” under a B-24 bomber. From the collection of John Campbell.

Even the German soldiers, when they captured American airmen, would take the A-2s and wear them, because the Nazi army never issued anything so cool. And after the Axis Powers were defeated in 1945, American airmen saw the A-2 as an absolute must-have.

“I’ve talked to people who, when they got back from the war, hung their jacket in the closet because they wouldn’t dare wear it in public.”“I know a guy here in town who graduated from flight school in 1949. By then, the U.S. Air Force [formed out of the Army Air Forces in 1947] was issuing nylon flight jackets,” Conway says. “He said that when he and his fellow recruits got out of flight school, the first thing they did was go to a surplus store and buy A-2 jackets because they didn’t want to look like new guys. The A-2 definitely took on a life of its own.

“This jacket was not only in the right place at the right time, it was also a very practical garment,” he continues. “I’ve talked to several World War II veterans who said they wore their unadorned jackets when they got home went back to school. A lot of vets wore them until they fell apart. So many A-2s didn’t survive the postwar years.”

An A-2 jacket worn by an American air gunner in the 86th Bomb Squadron, 47th Bomb Group. The dog was the squadron mascot, and the outline of Italy indicates were he served. From the collection of Jeff Spielberg.

While the A-2 lived on through trade and surplus, and was even reissued by the Air Force in the ‘80s, the painted flight jackets more or less died out. Both the end of the war and the introduction of standard-issue nylon jackets brought this hobby to a halt.

“The switch to nylon was a big factor because you can’t really paint on it,” Conway says. “I would say the loss of that paintable leather and then also the paring down in the forces brought an end to the painted leather jacket. When the U.S. Air Force was formed out of the Army Air Forces, the mentality of leadership changed. Air Force chief of staff Hoyt Vandenberg insisted that the airmen conduct themselves as gentlemen. And as the forces got smaller, it became much easier for the leadership to require the serviceman to comply with regulations and wear things in the way they were supposed to be worn.”

The artwork on this jacket depicts Hitler as a “Shifless Skonk.” The “Schifless Skonk,” misspelled on R.L. Parker’s jacket, was the name of a B-17G bomber of the 568th Bomb Squadron. The swastika marks a German aircraft destroyed, while the parachuter indicates Parker had to jump. From Arthur Hayes’ collection.

The end of the war changed everything for the young men who had enlisted to fight the Axis Powers.

“My father loved the military in wartime,” Maguire says. “He did not like it as much in peacetime because he had to play politics and he didn’t like sitting around the officer’s club and playing golf with ‘the brass.’ He liked going off and getting in his airplane doing his deal. He had real desire to stay in peacetime although he did continue in the reserves until 1958. In wartime, the focus changes.”

Painted flight jackets were always coveted by U.S. veterans, military men, and WWII and militaria collectors. But oddly enough, 30 years after America dropped the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japanese collectors got into the market for these A-2s, and drove the prices through the roof. Conway likens it to Americans who collect Nazi memorabilia.

“The Japanese, when they came in, were big buyers who paid premiums for jackets that didn’t have any problems,” he says. “But the A-2 is a garment, so this is a little absurd. The leather tended to draw moisture, and that was tough on the zippers, which commonly broke either from wear or just prolonged age. The knit cuffs and waistband were made with a high percentage of wool and susceptible to moth damage. But the Japanese ruled out a jacket being a premium if it had any kind of serious damage. So they raised the standard for collecting these, refining everybody’s approach.”

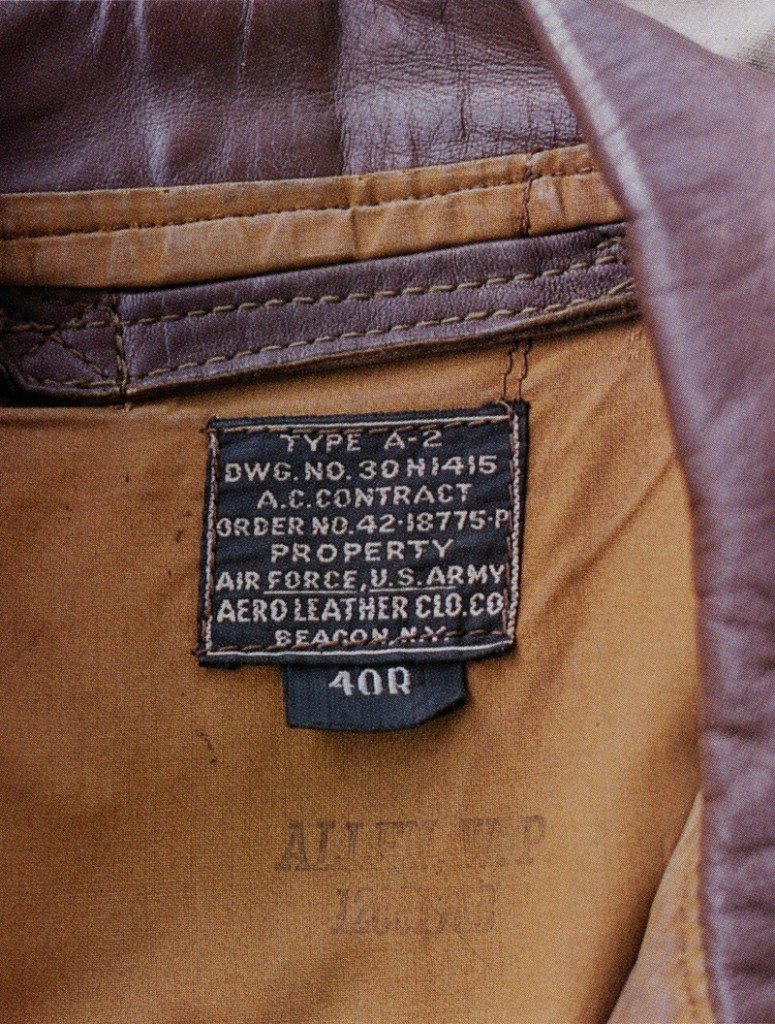

Some collectors and reproduction companies obsess over the details of the A-2, including the contract numbers, stitching, and dyes used by particular manufacturers, like Aero Leather.

Flawless painted flight jackets, which aren’t attached to anyone famous like the American Volunteer Group “Flying Tigers,” highly decorated airmen, or celebrities like Jimmy Stewart, will now sell for $3,000 to $6,000. But they’re rare. Of course, that’s created a market for counterfeiters who will buy an unpainted A-2 from the war, paint it, and artificially age the painting. That’s why Maguire and Conway are more interested in jackets that come with a picture of the airman wearing it. Obviously, some counterfeiters manufacture new jackets, but those are easy for a trained eye to spot.

Honest manufacturers, however, like Gary Eastman of Eastman Leather in London, whose book The Type A-2 Identification Manual, will be available online next week, make accurate reproductions of A-2s, down to the smallest detail. These high-end reproductions, like those offered by Eastman, Charles DiSpio’s New Jersey-based Buzz Rickson’s brand, and a New Zealand company called The Real McCoy, use the same thread and dyeing techniques of the early A-2 manufacturers. For people who are less obsessed with such details, you can buy a sincere tribute, a less-period-accurate leather jacket painted with pin-ups riding bombs and the like, for a more affordable price.

The Hump Pilots in the Air Transport Command flew supplies over the Himalayas, where the weather was their worst enemy. The camels indicate missions flown, while the camel facing reverse marks a turnaround due to engine trouble. From the collection of Willis R. Allen.

“Gary’s book is supposed to document every little variant in the production of A-2s, and the nuances between every company who made them,” Conway says. “For example, one company didn’t have brown thread to sew the A-2s together on one of their production runs, so they sewed them together with green thread. There are people who are very passionate about that particular variation. They create a neurotic list of criteria that these things have to meet, and when they hit that list of criteria, then it’s almost a situation where the price is no object. But a lot of times the criteria are so confining they rarely find anything.

“When Jon and I collect, we don’t care who made it,” Conway continues. “We don’t care if it fit and if the zipper was broken. You’re talking about a garment that’s 65 years old. Why would you expect the zipper to work? It’s not healthy to do that to yourself.”

“Doc’s Boy” G.H. Armstrong flew 30 missions on a B-24 bomber called “Puss-n-Boots” with the 577th Bomb Squadron. The winged 8th Air Force insignia was a popular motif for painted flight jackets. From the collection of Richard Peacher.

For Conway and Maguire, honoring the stories of the soldiers who wore these one-of-a-kind painted flight jackets was always more important than the jacket’s condition. Two of Conway’s most rare and prized A-2s belong to minority pilots who flew in World War II, a servicewoman in the Women Airforce Service Pilots and an African American pilot from the Tuskegee Airmen.

“My focus was really the people who wore them to remember them,” Maguire says. “It’s not about the jacket. For me, personally, if the jacket was documented with a photograph of the guy wearing it, it increases the value a lot.

“Wee Willie,” a bee carrying a red bomb, was the insignia of the 21st Bomb Squadron, 30th Bomb Group. The patch is sewn to the A-2 of Captain Earnest C. Pruett, who flew B-24 Liberators.

“Some books focus on how to identify a jacket made by the Cable Raincoat Company or Aero Leather, and who used olive drab stitching as opposed to tan. There are people who want to have one labeled by every contract number. I could care less about that. There are also a ton of history books on a certain battle with details about the troop movement and how many guys fought on each side. But I’m more interested in what the individual was doing: What was it like to be there? What did it smell like and what did they eat? What did that person feel?”

If an A-2 still has its name tag, it’s possible to research that soldier through federal records. In the past, Conway and Maguire would turn to veteran’s organizations, who would often help them track down a jacket’s history just with a nickname. But sadly, the World War II vets are dying off, taking their stories with them. For Conway, unraveling the mystery is part of the appeal.

“The first flight jacket I ever owned was a gift from a friend of mine who’s a World War II veteran,” Conway recalls. “He bought it in a clothesline sale at a school for a quarter in the 1970s. When he gave it to me, I was so elated. It had a B-17 bomber painted on the back, and 30 bombs, so we knew the guy had flown 30 missions. It had the tail code on the B-17 so we were able to determine it was the 92nd Bomb Group. I got hooked on unraveling the little mysteries, and also the je ne sais quoi of the leather aviators wore. Even the smell of that old leather captures your imagination because it makes you wonder where it went and who wore it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment