Traditional tattoo designs, like anchors, swallows, and nautical stars, are popping up on the arms and ankles of kids in every hip neighborhood from Brooklyn to Berlin, Sao Paulo to San Francisco. Yet these young land lubbers probably don’t even know the difference between a schooner and a ship, much less where the term “groggy” comes from. (Hint: Grog once referred to a watered-down rum issued by the British Royal Navy to every sailor over age 20.)

“There’s no way to take a tattoo home, except in your skin.”In fact, contemporary tattooing in the West can be traced to the 15th century, when European pilgrims would mark themselves with reminders of locations they visited, as well as the names of their hometowns and spouses to help identify their bodies should they die during their travels. “The attractions of tattoos for itinerant populations are quite obvious,” says tattoo-art historian Matt Lodder. “They can’t be lost or stolen and they don’t encumber an already heavily burdened traveler, so it’s not a surprise that they became inextricably linked with sailors.”

Though tattooing was already present in much of Europe, during the 1700s, the visibility of exotic voyages taken by the likes of Captain James Cook helped cement the connection between tattoos and seafaring men in the popular media. The English word “tattoo” is actually a descendant of the Tahitian word “tatau,” which Cook recorded after a stop on the island while travelling in the South Pacific. European explorers frequently returned with tattooed foreigners to exhibit as oddities in the West, like Omai, the native Raiatean man Cook presented to King George and members of British royal society. Such publicity soon ignited a more widespread fascination with body art.

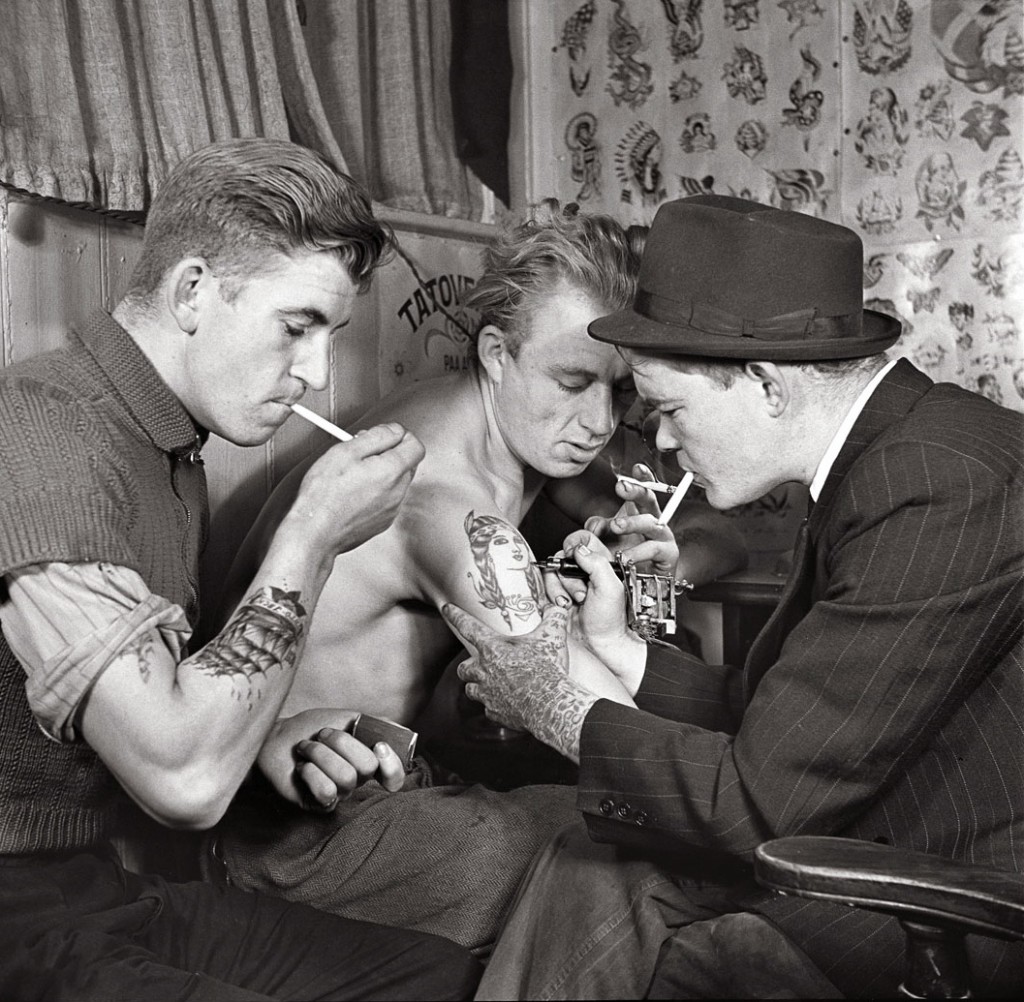

Top: A scene from Tattoo Jack’s shop in Denmark, circa 1942, from the book “Danish Tattooing” by Jon Norstrøm. Above: An etching of “Prince Giolo,” a tattooed slave captured from the Island of Miangas by William Dampier’s expedition in 1691.

Body art was particularly well-suited to the transient and dangerous nature of life at sea. “These sailors were traveling the world, and wanted to bring back souvenirs from places they had visited,” explains Eldridge. “Aboard a ship, you don’t have much room to carry fancy souvenirs, so you end up getting tattoos as travel marks.” By the late 18th century, navy records show that around a third of British and a fifth of American sailors had at least one tattoo, while other accounts reveal that French, German, and Scandinavian navies were also fond of getting inked.

Two vibrant nautical designs by tattoo pioneer Samuel O’Reilly.

The variety of designs matched each and every danger aboard a ship. “Sailors would get things like a pig and rooster on their feet to keep them from drowning,” Eldridge says. “They would have ‘Hold Fast’ tattooed on their knuckles so that when they were in the riggings, their hands would stay strong. They would get hinges on their elbows to keep them from having rheumatism and arthritis, and sometimes they would even get a little oil can tattooed above the hinge so that the hinges would stay lubricated.”

Though the meanings of such tattoos have often shifted according to context, for some sailors, crosses on the feet were an attempt to ward off sharks, swallows were associated with a safe voyage home, and nautical stars were linked to accurate navigation. “The stereotypical images we think of as classic tattoo designs today—pierced hearts, swallows, anchors, suns and moons, mermaids, naked women, memorial images such as graves, and religious imagery such as crosses—were all common motifs by the time militaries started recording the tattoos of enlisted men,” says Lodder. “All these designs can be found in naval handicrafts and folk art of the same period, too, etched into tobacco tins, carved into whalebone as scrimshaw, or included in love-tokens made from beads and shells.”

Captain Elvy, who worked as a sideshow attraction, displays his beautiful back piece designed by “Sailor” George Fosdick.

Tattooing really took off after 1870, when the first professional tattoo shops opened in the United States and Great Britain. In America, the earliest tattoo parlor is attributed to a German immigrant named Martin Hildebrandt, who opened his business in lower Manhattan. Hildebrant practiced the slow art of giving tattoos by hand, using a row of needles attached to a wooden-handle which was rapidly tapped upon the skin. At the time, tattooing was an artisan trade typically learned by working with a well-established tattooer. “It was a craft,” says Eldridge, “usually learned through an apprenticeship. It’s exactly the way a seamstress would hem your pant cuff with a needle and thread rather than a sewing machine. They learned to manipulate the needle into the skin and to create designs by hand.”

A photograph of Percy Water’s tattoo machine and an advertisement from 1928, which mimics the artistry of hand-drawn flash.

This system of shared knowledge also helps explain why nautical designs were commonly copied and spread from artist to artist. “A lot of classic symbols were passed down from one war to the next, even going back to the Civil War,” explains Eldridge. “The tattooer might take an illustration, an etching, or a block print, do a drawing from that design, and put that on his sheets of flash,” the name for the paper ads tattooists created to show off their wares. Another tattooist would see a design and, in some cases, do a tracing directly off the person’s arm. “The designs were copyright-free and in the public stream,” Eldridge adds.

Left, a 1907 portrait of Mrs. Maud Stevens Wagner, the wife of tattooist Gus Wagner. Right, a sailor with a patriotic chest piece by West Coast tattooist Bert Grimm.

As military enlistment escalated prior to World War II, the American Navy caused another inadvertent boom in tattooing. Decades before, the U.S. government had issued a pamphlet with a passage requiring incoming recruits to fix any obscene tattoos, which primarily meant drawings of nude women. During the ’40s, this passage was a godsend for tattoo artists, as young men scrambled to censor their bodily markings so they could enlist. “It’s been just like old-home week around here since Pearl Harbor,” said Charlie Wagner, the famous New York tattooist. “Could you imagine how a store clerk would feel in a town where everybody’s clothes wore out at the same time? That’s how I’ve been feeling. For going on 50 years, I’ve been turning out tattooed ladies, most of them naked, and now all I do is cover them up.”

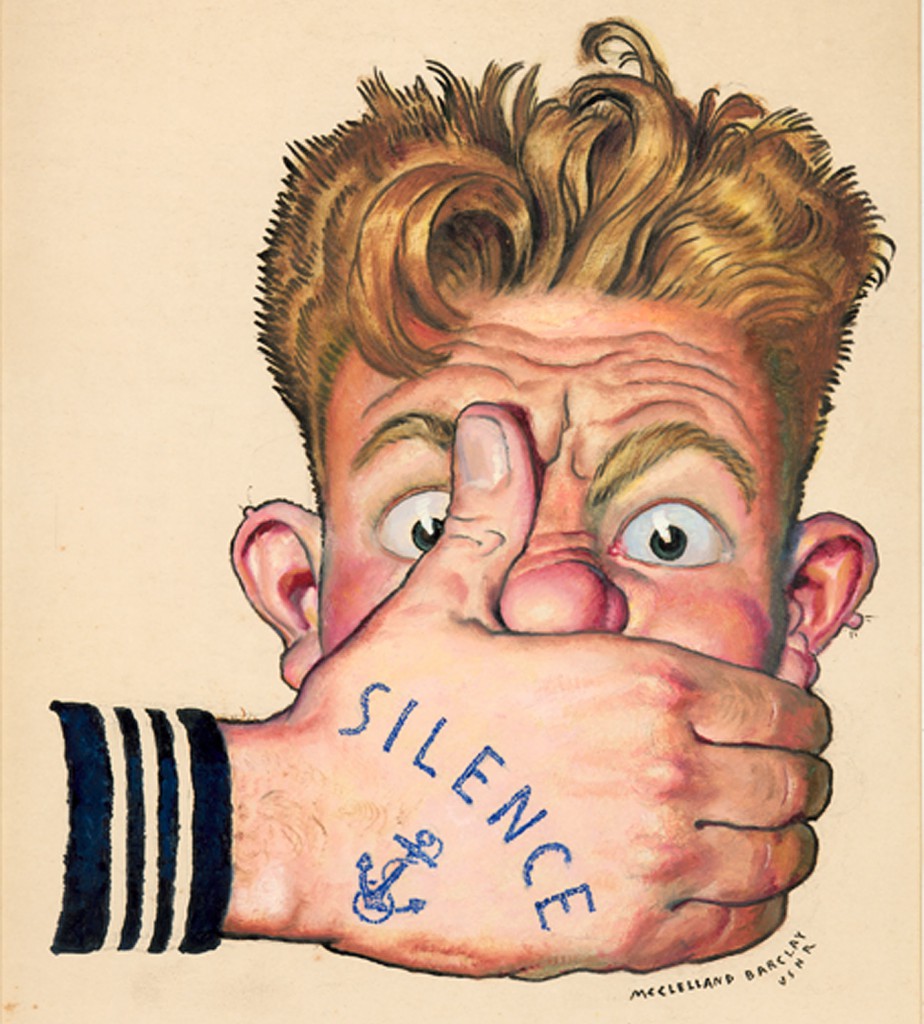

Even official U.S. Navy posters incorporated the ubiquitous nautical tattoos, like this image from the “Loose Lips Sink Ships” campaign of the ’40s.

Lodder believes that Sailor Jerry’s influence on contemporary tattooing can’t be overstated. “He was an incredible draughtsman and artist who made use of the technical limitations of the medium to produce incredible designs. His pieces are complex enough to have life and energy, but simple and stripped-down enough that they look great in the skin, are readable from a distance, and age superbly.” Eldridge agrees that Sailor Jerry had a profound influence, possibly most distinguished by his ability to execute designs that looked even better on skin than they did on paper.

“There’s so much discipline in his line drawings,” Lodder adds, “but that tight style does nothing to reduce the sexiness of his pin-ups, the energy of his cartoons, the anger of his political designs, or the romance of his renditions of Hawaii. His style, a re-imagining of American tattooing of the 1920s and ’30s into a cleaner, bolder version for the 1950s and ’60s, established the ‘traditional’ tattoo in the late 20th-century imagination.”

A sheet of Sailor Jerry’s flash shows his expressive, clean-lined style.

“When the first tattoo shops opened in the late 1800s, they were already old-fashioned.”One of the most visible of these affluent clients was King Frederik IX of Denmark, who took the throne in 1947. “He was from a Scandinavian country that treasured its seafaring tradition, so he went to sea at the age of 12,” says Eldridge, “It was almost a requirement for the king to understand how the Navy operated, because back then, whoever ruled the oceans ruled the world.”

In Britain, the expansion of professional tattooing was partly due to the trendiness of tattoos among the aristocracy following the Prince of Wales’ acquisition of a “Jerusalem Cross” during a trip he took to the Holy Land in 1862. “All the major London tattoo artists around the turn of the century made much of their celebrity clients—kings, princes, barons, music hall stars and entertainers—and their adverts were placed among those for champagne and high-end cigars in the tabloid press,” Lodder says.

Left, traditional American designs featured on Col. Todd’s flash in 1963. Right, King Frederik IX of Denmark shows off his tattooed torso.

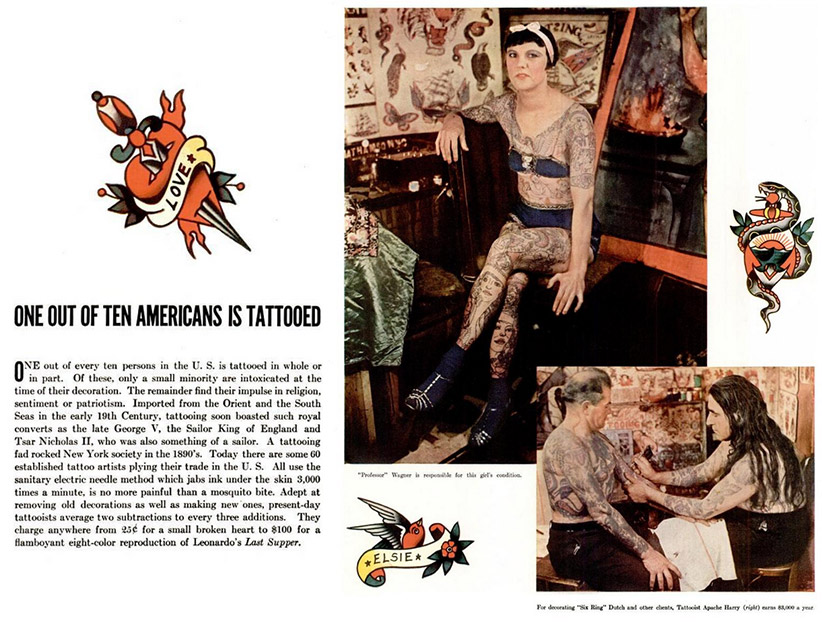

In the 20th century, popular media outlets repeatedly hyped this dual view of tattooing as both a chic fashion for the wealthy and an expression of vile barbarity. A Vanity Fair article from 1926 claimed that tattoos had “percolated through the entire social stratum; tattooing has received its credentials, and may now be found beneath many a tailored shirt.” Ten years later, Life Magazine published an article that claimed 1 in 10 Americans had a tattoo.

After extensive research, Lodder has come to realize that “even when the press praised tattooing as newly respectable, newly fashionable, and a spectacular and ancient art form, as has happened every decade since the 1880s, other corners of the commentariat would decry tattooing as primitive, barbarous, and uncouth. Rather than waxing and waning in social acceptability over the 20th century, it’s more accurate to see these two strands as running in parallel.” Though sensationalist articles were meant to sow the seeds of controversy among readers, the majority of whom certainly did not have tattoos, they often reveal this repeated fallacy in the media coverage of tattoos.

From Eldridge’s perspective, our ambivalent views about tattoos in Western culture stem from engrained religious beliefs. “I really believe that prejudice is rooted in religion, and it’s going to take a long time for that to disappear,” says Eldridge. “Our country is a very religious, Christian country. Leviticus and all those Bible verses about ‘marking the body’ continue to hold a lot of sway.”

Lodder also emphasizes the importance of eugenics and racial hygiene theories at the end of the 19th century, which allowed scientists to equate tattooing with an uncivilized past. “The idea that you can judge a person’s moral character and worth by their appearance really took hold in intellectual circles, and tattooing was swept into that rhetoric. Even as articles appeared in the press about the future King George V getting tattooed in Japan, or praising Japanese tattooers for their highly developed skills, the scientific literature asserted that tattooing was barbaric and only for those of lower means—a strange ahistorical, counter-factual set of arguments which persist to this day.”

Despite continued stigma, in the United States the number of individuals with tattoos is definitely growing. A recent Harris poll found that nearly a third of the population between the ages of 18 and 39 has a tattoo. Eldridge traces the rise of contemporary tattooing to the debut of MTV in the early ’80s. “You know how television is in America: If it’s on television, then it is somehow validated. We’ve always emulated celebrities and musicians, inheriting their styles, clothing, cars, and everything else. So I think once MTV appeared and all these musicians were visible with their tattoos, it was only natural that their fans would start getting tattooed.”

Temporary tattoo products have long banked on the trendiness of sailor tattoos, as seen in this 1940s booklet. Image courtesy Ballyhoo Vintage.

“The rise of consumer culture along with the embrace of unadorned, streamlined modernist aesthetics in the 1950s also undoubtedly contributed to tattooing’s fall from grace,” Lodder says, “until its subsequent revival in the 1970s. Once again taking the lead from their grandparent’s generation, tattooing began to rise in popularity through the mid-’70s and ’80s, though in a visual-culture context propelled by postmodernism, conceptual art, and the impact of the avant garde, the design choices were increasingly eclectic, making the ‘traditional’ designs seem somewhat old hat.”

Which brings us to the present, and the hordes of young urbanites whose flesh is marked with symbols of mariners from centuries past. Eldridge finds that brands like Christian Audiger’s line of Ed Hardy clothing or Sailor Jerry Rum have had “a tremendous effect on the current popularity of traditional tattooing.” In 1995, Hardy also published “Flash from the Past,” which Lodder believes prefigured the revival of classic American tattooing.

But perhaps the most straightforward reason for the resurgence in traditional tattoos is the nostalgic allure of a fantasy life at sea, especially at a time when the present seems rather bleak. “Traditional American designs are steeped in romance,” says Lodder, “and come with a combative rhetoric of tradition, lineage, craftsmanship, and cultural memory, as well as a loudly defended sense of what tattooing is, and what it should be.”

Matt Lodder’s “Know More” hand tattoos blend naval superstition with academic sensibility

No comments:

Post a Comment